Presences of Arctic Homelands

rin Ggaadimits Ivalu Gingrich is an emerging Alaska Native artist who is already garnering widespread accolades along with early career support from the Native Arts & Cultures Foundation. She is currently a SITE Scholar and pursuing an MFA from the Institute of American Indian Arts. During the bustle of early summer, I interviewed Ivalu over the phone to learn more about her work.

“I have this really deep love and deep gratitude for what has kept me, my Elders, my people, and my Ancestors, tied to the north and tied to these places that I get to call homelands,” she explained. As Ivalu spoke, she occasionally emphasized a word by gently drawing it out, expanding her soft rhythmic tone. Slight interference distorted the call. “And so much of that beauty in their wild being is something that I’ve always been captivated with.”

Wood carved from a unique hand and perspective represents the ancient time from which the art practice was derived. The reiteration flows from a voice rooted in her homelands and continues to bear the markings of both the present and the past.

SITNASAUQ ASIAT (NOME BLUEBERRIES)

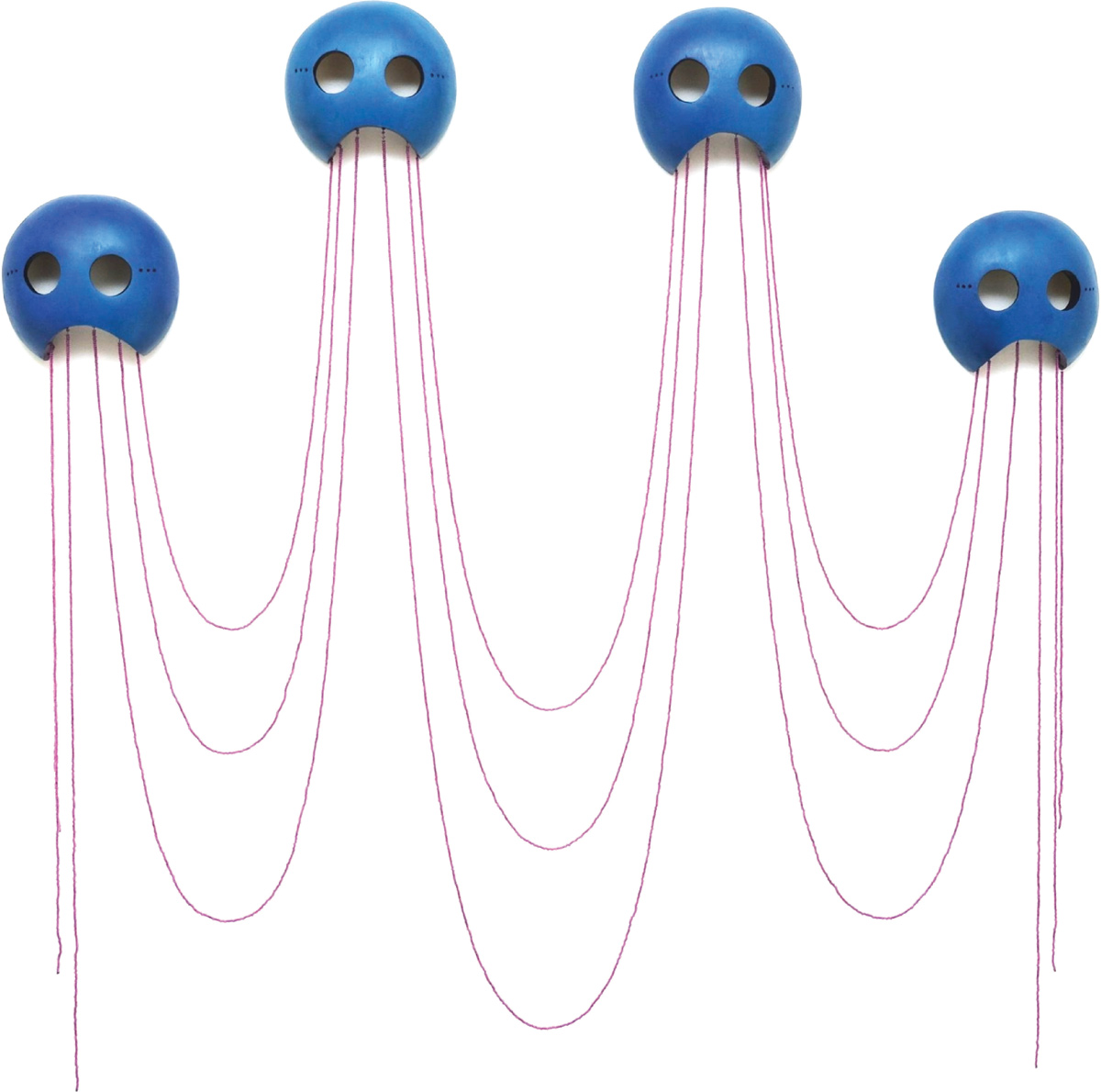

“I try to represent the gift of their presence and the ability for them to be with us here because they are a part of what makes these places home and we could not exist without them. Representing them with masks has, for me, been the most effective way to do that.”

Itigiat (Weasels) is a group of three masks that look like they are taking a momentary breath between mischievous tasks. Their boxy yet sleek heads are draped in strands of thick white beads, while a few discrete black dots on the end provide an interesting contrast. This effect characterizes their transformation into a blanched winter coat with a tail darkened at the tip that stands out against the snow as the Ermine playfully darts along.

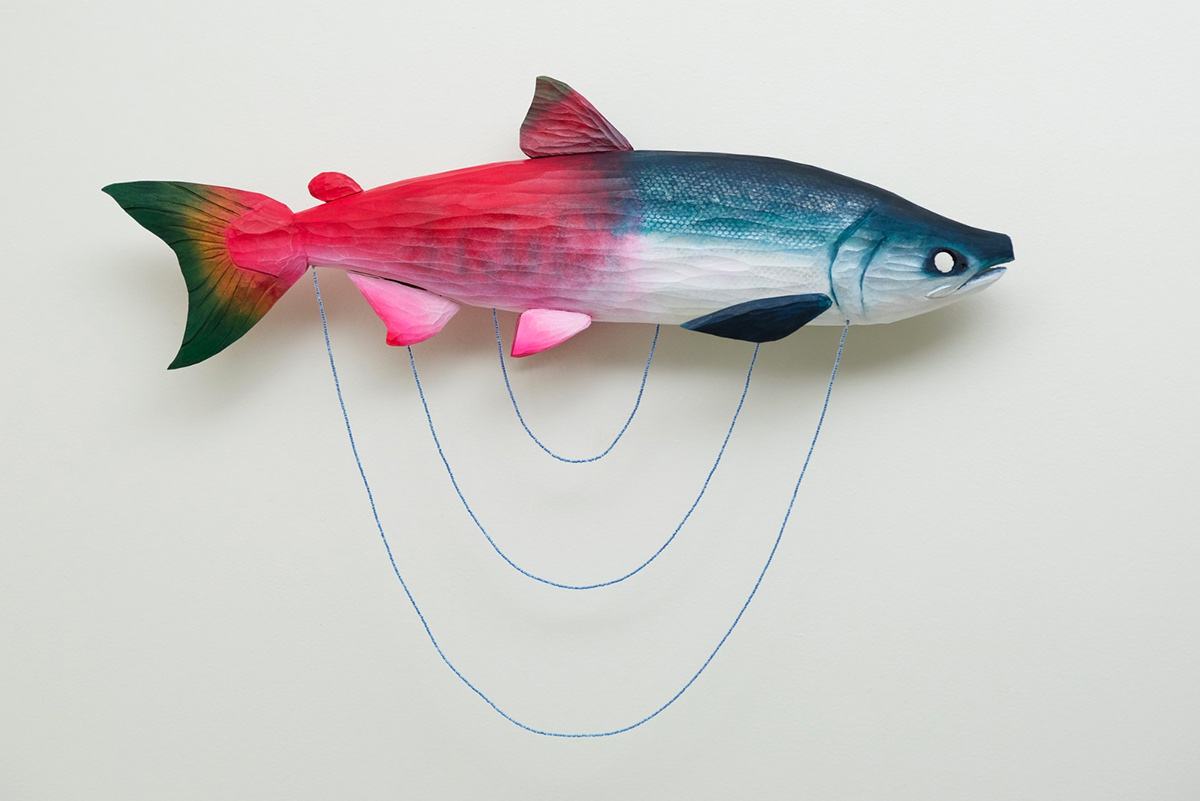

SHIFTING IQALUKPIK FROM GGASILAT 1

The thematic work of Ivalu intricately interweaves the intersection of the gift of life dying so other life can live. Natchiq (Seal) holds a fish’s spine in its mouth, while the grain of the mask’s wood swerves up the bridge of the nose in the form of multiple faint lines before disappearing into the top of the skull. The curvature and expression of the carving make it look like it is changing shape while simultaneously staying present. Strands of beads run through the opening of the mask’s hollow eyes and the emptiness that it exhibits creates the capacity for life to enter, which is replicated throughout her artwork.

NESTING TITIRGAK FROM TROTH YEDDHA WITH MANNIK

Ivalu continued: “The beads give the work a fluidity and a presence and an etherealness. You get to experience when you’re with the piece physically because they interact with the space, they interact with you and make great beautiful movements and small moments that are really, valuable to me to see others experience.”

IQALUKPIK FOR MY FRIENDS

Regarding her use of beads, Ivalu said, “It also adds an element of femininity that really seeks to balance this historically masculine art form. And that’s important to me as well. I learned to bead before I learned to do really anything else. It just creates this really important balance and element and this combination.” She explained that combining the two mediums also creates a wholeness in her work as an Inupiaq and Koyukon Athabascan artist “Carving has this deeper connection to one Indigenous history and beadwork has this connection to my other Indigenous heritage.”

TUTTU (CARIBOU)

In contrast, Ivalu achieves the same effect using smooth surfaces to amplify the work as much as rough ones, in pieces such as Itigiat (Weasels), Pammiuqtuuq (River Otter) and her berry series. Historically, many Alaska Native masks had a distinctively chiseled texture to enhance the experience in front of an audience in a dimly lit room. By capturing light in unique angles, the shadow-speckled mask added another dimension to the performance when worn. The more contemporary and standard smooth look partially emerged due to the demands of Settler traders; collectors sought a more “finished” look.

“I really start my work with intention. I know some carvers; they’ll get material and they’ll let the material speak to them first. I typically approach my material with this intention of, what I want it to be, and I ask it for that permission to let me get to make it into what I want.”

MOLTING NATCHIQ FROM SITNASAUQ

Ivalu continued further: “Taking my time to tend to my practice and develop concepts and ideas of making and studying work of other artists and ancestral artists. I think that I’ve taken my time with making masks and getting to a place where they’re not just representations of presence but going to be adding that element of transformation to these pieces so that they can be activated in the ways that historically, they have been.”

“Last year I made a seal mask that is suppose to represent the molting process that seals go through. So, it kind of is one of those pieces that I get to build on and build a deeper communication with that representation.”

This freedom of working in an intergenerational and interspecific continuum and allowing time for growth is visible in the spatial relationship of subject and object, wherein the two are interchangeable and simultaneous. Ivalu represents various beings of the North, often in a transformative state, watching the observer. Within this subtlety rests a relationship with place since time immemorial with no apparent separation of the onlooker, participant, natural beings, elements and humans. The cultural reverence and mutual dependence of these life forms that compose her ancestral home are incorporated into a visual language. However, some nuances and ethos may be lost in the translation of a Settler gaze.

A distinguishing strength of Ivalu is rooted in her sovereignty as a Native artist. Her work does not necessarily respond to Colonialism. Instead, it simply and profoundly exists as Indigeneity. Because of this cultural perpetuity, the messaging in her work is as much a part of this contemporary time as it is of the ancient past.

A predominantly non-Native liberal-leaning audience often expects or interprets Indigenous artwork to primarily focus on climate change and eco-consciousness. However, this assumption is often made without fully engaging with or genuinely listening to our perspective when we address such topics. This also stems from a cultural bias that environmentalism is detached from the moment-to-moment co-existence of ever-evolving death and rebirth of the natural world.

The artwork of Ivalu prioritizes, as she says, a “deep love and deep gratitude” for cultivating healthy relationships and fostering respect and appreciation for mutual existence. In fact, this way of being enabled her Ancestors to reside in the Arctic, nourish and pass on the life that runs through her. Although the discourse of her work speaks to climate change, it extends beyond this singular issue and strives to delve into the underpinnings of matters frequently overlooked by Settlers because it stems from an Indigenous worldview and is not centered in theirs.

The artistic voice of Ivalu is so powerful, that it almost operates on a haunting frequency. Her vision is highly expansive, creating the capacity to transcend these cultural gaps, especially for those willing to listen.