Peter Williams works to restore

Indigenous peoples’ rights

to their relationships with animals

Sitting on the cold metal seat of my skiff, moving with the boat’s body as it pounds and skips over the ocean. The outboard hums. A gray horizon produces the illusion that the sea and sky are separate. Salty wind moves across my face, the blessing from an invisible hand. Zipping past inlets, winding through islands the seascape unfolds in front of me. Nearing floating birds, they take to the air. Pulling away from the bow of my boat showing, the superiority of their wings and muscles compared to the technology I can afford to buy, I get the sense there is something beneath me. Moments later a whale breaks the surface, blasting the remnants of held breath. The voice of my deceased Father tells me to be careful.

Clink.

The hook bounces, the ocean swells, the rope moves in the surf. I start to pull. My rifle is in a dry bag strapped over my back. I give the rope slack, as the wave ebbs the bow drops a few feet. Foam rushes down barnacles, blue muscles and seaweed. The sea takes a calming breath, and with it I jump onto the rock. The stretched rubber in my anchor line retracts.

Crouched with eyes forward, gear in hand, slowly moving toward the seals. My heart races. Working with the curvature of the rock to stay hidden, I look for an elevated flat surface to use as a rest. Reining in my mind and steadying my nerves, the sound of the sea muffles as I put on my headphones. Slowly rising I turn, laying down my green life jacket in front of me, gently resting the rifle on top of it. Stretching my body out by leaning against the rock. Spreading my feet shoulder width apart I look through the scope. The rest embraces the weight of my rifle. The seal strains its neck out of the water. Sleek wet fur glistens. It has spotted me.

Spending a lot of time in nature and with death has educated me in ways that no classroom ever could. Death is as special and important as life. Perhaps even more so, if one wants to view them as separate.

My journey as a practitioner and culture bearer of traditional Alaska Native knowledge and art began at age eight, when I attended Dog Point Fish Camp. There I engaged in traditional foods harvesting, arts and cultural protocol. The loss of my Father at a young age to an alcohol-related boating accident while being raised outside of my culture added to the pain of intergenerational trauma and the confusion of not knowing what it was or where it stemmed from. I began to internalize oppression, enduring suicidal ideation for over a decade and living inside a bottle, praying to a God that I was not sure existed for help. I knew if I kept walking the path I was on, I would soon be dead. Regardless, I understood that a life of addiction and self-hatred was no life at all.

Returning home, something woke inside of me. The ocean, the forest, my culture and the gifts of sobriety and spirituality provide an embrace. I follow the footsteps of my Ancestors.

Alaska Native Culture embodies reciprocity between human, plant, animal and spiritual worlds. I assume responsibility for this by practicing an endangered art form disrupted by colonization — sewing the skins of marine mammals and fish. My process perpetuates an Indigenous protocol of developing a personal relationship with ‘the materials of place’: I source by hunting and fishing; I alter by tanning; I construct by the time consuming yet cathartic labor of hand sewing, each stitch a prayer. Before a hunt I smudge and pray, asking the animal for its life; after the hunt I honor the animal by giving it its last drink of water per Yup’ik custom. Catches are shared as nourishment for my community, then repurposed into a reflection of Native experience.

My work as an artist developed concurrently and often overlapped with my efforts to introduce Alaska Native hand-sewn seal and sea otter fur garments into high-end fashion, rooted in the economic need of Alaska’s Indigenous communities to ensure the continuity of this practice. We live in a capitalist, colonial world, and unfortunately I can’t take a seal carcass down to the city office to pay my utilities bill — I must do so in USD. At craft fairs I frequently see Elders selling beautifully constructed, hand-sewn sealskin animal figures for the price of a pizza. I’m ashamed that our Elders’ unique skill sets and knowledge are so undervalued, and am reminded of the fact that if our tradition of marine mammal artwork remains unprofitable within the Western capitalist framework, future generations of Alaska Natives will elect not to practice it. My 10-year pursuit of introducing seal and sea otter garments into high-end fashion is rooted in this need to ensure the continuity of this practice. I broke ground by presenting a collection at New York Fashion Week and Fashion Week Brooklyn in 2015 and 2016, leading to profiles in The Guardian and The New York Times.

The conservation of seals and sea otters is governed by the Marine Mammal Protection Act in the United States, which prohibits them from being hunted by most US citizens. Coastal Alaska Natives like myself are exempted from this prohibition, as we have sustainably and respectfully harvested these species for thousands of years. Marine mammals are a foundational part of our culture; studies by US Fish and Wildlife and marine biologists have demonstrated that our harvest does not negatively affect the species’ population levels, as published in the sea otter Stock Assessment Reports (SARs).

The SARs begin the Population Size section with the following:

“Historically, sea otters occurred across the North Pacific Rim, ranging from Hokkaido, Japan, through the Kuril Islands, the Kamchatka Peninsula, the Commander Islands, the Aleutian Islands, peninsular and south coastal Alaska, and south to Baja California, Mexico… In the early 1700s, the worldwide population was estimated to be between 150,000… and 300,000 individuals… Prior to large-scale commercial exploitation, indigenous peoples of the North Pacific hunted sea otters. Although it appears that harvests may have periodically led to local reductions of sea otters… the species remained abundant throughout its range until the mid-1700s. Following the arrival in Alaska of Russian explorers in 1741, extensive commercial harvest of sea otters over the next 150 years resulted in the near extirpation of the species.”

I regularly encounter the erroneous and widely-held impression that sea otters are endangered in the United States, and that Indigenous harvest contributes to their decline. In actuality, they are not classified as ‘endangered’ under the US Endangered Species Act, and research by marine biologists show that subsistence harvest does not have a negative effect on sea otter stocks.

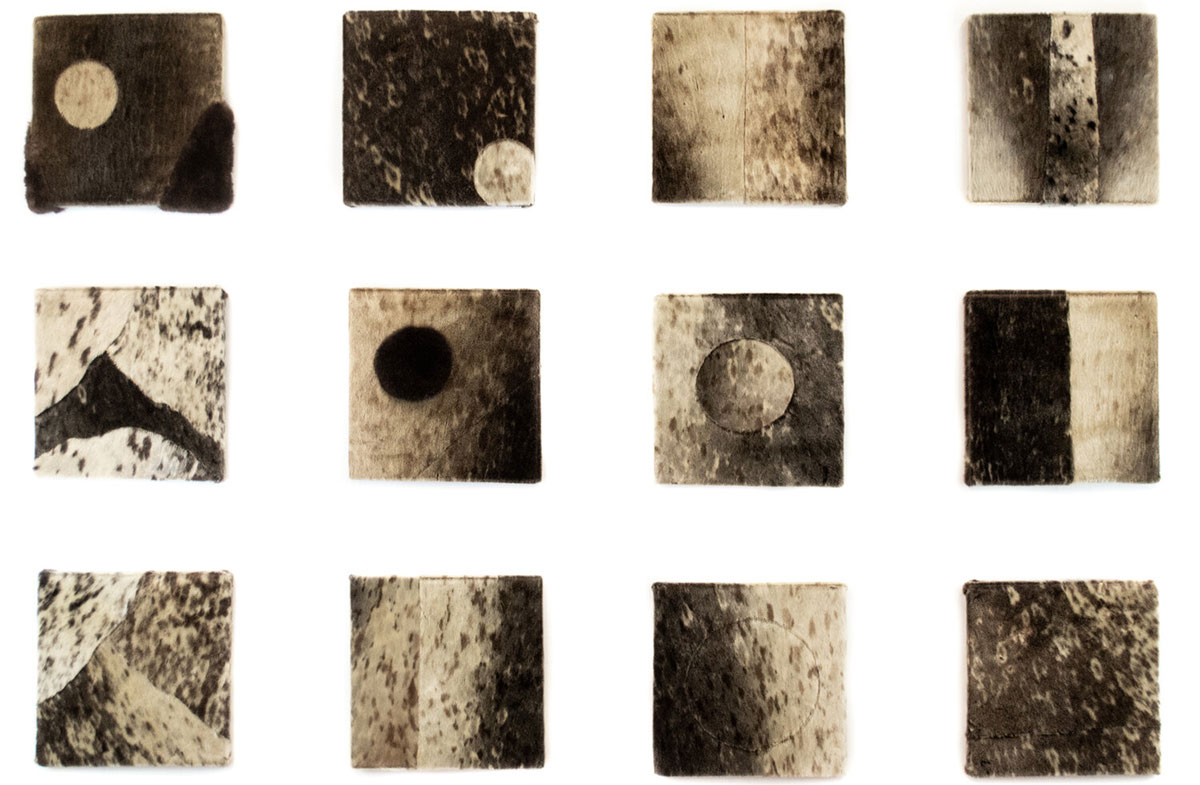

To address those misunderstandings I created a series of five artworks, each representing one of the US sea otter stocks using federal data from the latest published SARs. The Washington (Northern sea otter) stock has an estimated population of 1,806. While California (Southern sea otter) stock is estimated at 3,272. It and the Southwest Alaska (Northern sea otter) stock are the only stocks listed as ‘threatened’ under the ESA. No hunting of the Washington and California stock is currently taking place, because the exemption in the MMPA applies only to Alaska Natives; other coastal Native Americans outside Alaska are still legally barred from harvesting sea otters. An area in need of redress as various Indigenous groups across the coast in what is now called the United States, including Hawaii had a traditional relationship of utilizing marine mammals, an inherent right not currently recognized by Congress.

The Southwest Alaska (Northern sea otter) stock has an estimated population of 54,771. Although it is listed as ‘threatened’ under the ESA, the SAR states “areas within the stock that show signs of continued population declines have little to no record of subsistence harvest.” Unknown ecological factors are believed to be the cause of the stock’s decline; not Indigenous subsistence. Southcentral Alaska (Northern sea otter) has an estimated population of 18,297 and Southeast Alaska (Northern sea otter) stock of 25,712. Totaling the five US stock population estimates equals 103,858 sea otters.

In the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (9th Cir. 1992): Boyd Didrickson and Marina Katelnikoff Beck v. United States Department of the Interior pointed out that in Alaska “although once virtually extinct, the sea otter has rebounded in recent times” and they neared, if not exceeded, historic levels. The court case symbolically and literally represents the continued Alaska Native rights struggle in lacking agency for self-determination and the settler colonial impediment to Indigenous people’s ability to practice a traditional lifestyle in the present day. By opposition from the US Government, US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and The Friends of the Sea Otter, Greenpeace, Alaska Wildlife Alliance, and the Humane Society of the United States collectively referred to as FSO in the case. They challenged the newly recognized rights of Alaska Natives to harvest and work with sea otters.

The case involved “Marina Rena Katelnikoff Beck, an Aleut living on Kodiak Island… where… in May 1985, the FWS agents confiscated items including growling teddy bears, pillows, hats, mittens, and fur flowers… on the basis that they did not fall within the native handicraft exception because they were not of a nature commonly made or produced prior to the passage of the MMPA in 1972.” In June of 1986 Boyd Didrickson (Tlingit) intervened as Plaintiff-Intervenor, as a sea otter fur hat he made was confiscated by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Because it “contained metal snaps and zippers, which did not qualify as traditional, according to the FWS… Didrickson was also informed by the FWS that the offer for sale of some of those items to non-Natives would continue to be illegal.”

The judge was concerned with the requirements that the items be “commonly produced on or before December 21, 1972.” He described the Government’s position on what uses of sea otter pelts were permissible as a “moving target,” and expressed “doubt … that the Government has fully and adequately considered the possibility of establishment of bona fide, eighteenth century uses of sea otter pelts which would not be precluded by the clear language of 50 C.F.R. § 18.3.”

The Government began a review of the regulation by publishing a proposed amendment to ban all takings of sea otters for purposes of creating handicrafts or clothing for sale on the ground that Alaska Natives had not “commonly produced and sold handicrafts or clothing from sea otters within living memory.” The litigation was stayed pending issuance of a final rule.

The Alaska Natives vigorously contest this factual determination on the basis of extensive evidence of centuries of use by Alaska Natives of the sea otter for many purposes, including clothing, handicrafts and items of barter and trade. They point to the fact that after the Russians’ occupation and their discovery of the uses of the sea otter in 1742, the Russians, using the Alaska Natives to harvest the sea otter, banned the sea otters’ use by Alaskan Natives. This restriction continued after Russia sold Alaska to the United States, as a practical matter, because their American traders who dominated the sea otter fur trade acted just as the Russian predecessors had. Through excessive hunting of the sea otters, they virtually became extinct by 1899. From then on, various restrictions by the United States on the harvesting of sea otters precluded Alaska Natives from using sea otters as they had done for centuries. The Alaska Natives pointed out that for centuries the sea otter had been an intrinsic part of the subsistence way of life of the Alaska Natives. The sea otter had been used for items of clothing, rugs, blankets, bedding, and items of handicraft that were traded and bartered by the Alaska Natives. The centuries of use were interrupted during the period in which Natives were banned from using the sea otter by the Russians and, in turn, by the United States prior to 1972.

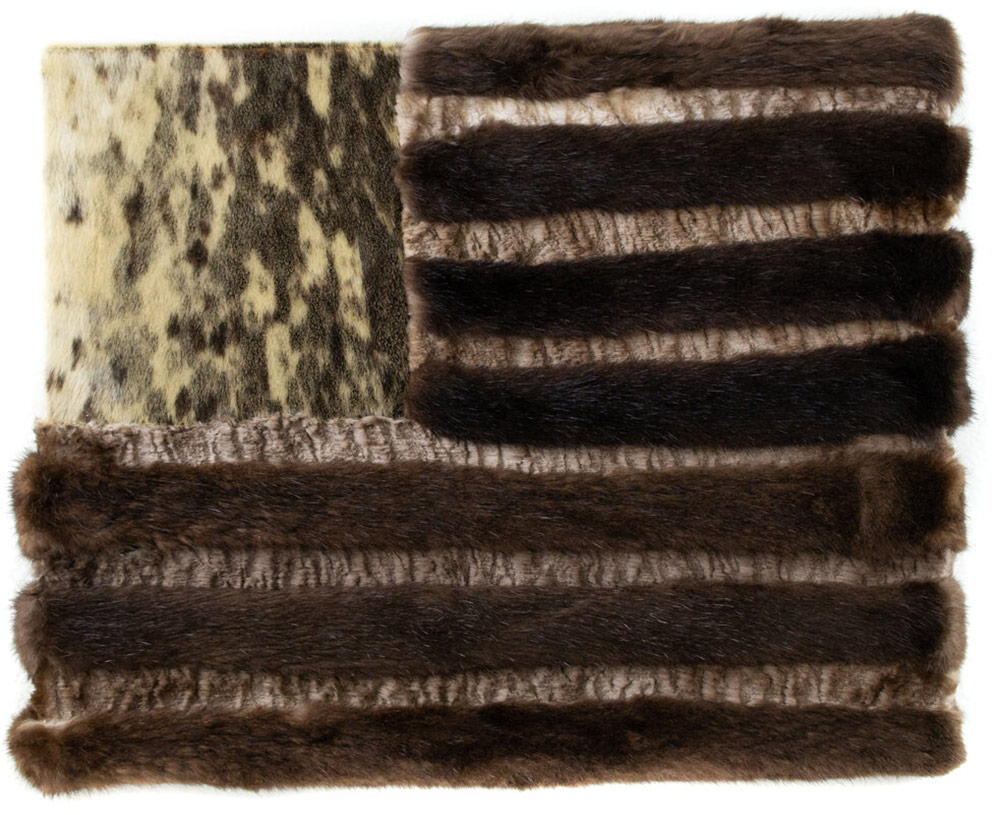

In 2018, I hand-sewed an American flag out of sheared sea otter and seal to talk about how Russian colonial powers prized sea otter fur, and lust for this ‘soft gold’ led to genocide, land theft, and exploitation of Alaska and its Indigenous groups. This oppressive power dynamic continues through American occupation today. Although Alaska Natives theoretically have exclusive rights to hunt and work with marine mammals, non-Native people are still creating the definitions and regulations of who qualifies as Alaska Native and what qualifies as Native art.

Once under the occupation of colonial forces, Indigenous ways of life were disrupted and made illegal under Russian, and then later United States, laws. In efforts for reconciliation, international and federal laws, along with treaties, have been passed in recognition of the inherent rights of Indigenous peoples. The rights Natives upheld since time immemorial would later be understood by the United States and international governments. Nothing was “given” to us because we always had these rights regardless if settler colonial laws permitted it. Legal concessions were made to protect these rights such as the exemption for Alaska Natives in the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Self-determination and protection of these rights are still an ongoing struggle for Alaska Natives, Native Americans and Indigenous people globally.

I responded with, “No. I am telling you it is.”

The work of Charles C. Mann and William Maxfield Denevan involves the concept of the Pristine Myth which stems from the falsity that Indigenous people were not drastically and purposely altering their environment on a large scale prior to colonization. It takes form in Western environmentalism as viewing and aspiring that nature must be “wilderness” “pristine” and “untouched” by humans, and plays into a long-standing, dehumanizing view that Native impact on nature was like that of grazing animals. It discounts tens of thousands of years in which Native people have been managing, utilizing, significantly altering, and having a relationship with the environment.

“American Indians and National Forests” and “Inhabited Wilderness,” two books by Theodore Catton, explore this culture clash and competing worldviews on the mutual goal of conservation and the devastating impact of the National Park movement on Tribal groups. These conflicts on cultural ways of interacting with nature and what demographics write and pass such legislation are exemplified through the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the exemption for Alaska Natives.

The very confusion many Western non-Natives have in trying to reconcile a protected species being hunted in the name of Indigenous rights is evidence of this ideological culture divide extending beyond the realities that sea otters are adorable and were nearly made extinct during the colonial controlled fur trade. This speaks to a foundational worldview that in order to conserve and honor nature sections of it must be “preserved” with no human interaction except in the form of tourism and recreation.

This is in direct contrast to Indigenous ways of knowing that emphasize the importance of co-existing with nature in a daily form of interaction through reciprocity. Within this ideology, hunting a sea otter while in the realm of conservation is not seen as a conflict, but the opposite. It’s through a constant, holistic, dependent relationship that involves both the death and appreciation of the sea otter that ensures it will be around for many future generations.

“All of life is considered recyclable and therefore requires certain ways of caring in order to maintain the cycle. Native people cannot put themselves above other living things because they were all created by the Raven, and all are considered an essential component of the universe,” says Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley (Yupiaq) in “A Yupiaq Worldview.”

This Native perspective and juxtaposition are not only applied to Western conservation but also industrialization and extraction. I produced a documentary called “Harvest: Quyurciq,” and in it Teri Rofkar (Tlingit) says, “When the Russians were here, there was just such an abuse of what in Western culture is called the resources… The sea otter is our resource, the mountain goat are our resource, our salmon are our resource. And if we replace that word ‘resource’ with relationship, I think it embodies more the Native perspective.”

Environmental racism, beyond disproportionately polluting Native lands and bombing it for military exercises, pushes a White lens of how Natives “should” or “should not” interact with nature. Rooted in a self-created position of power dating back to the Doctrine of Discovery and concepts of dominion, Settler Colonial resistance to Alaska Natives practicing this cultural way of life remains in the present day.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz writes in her article The Doctrine of Discovery, “In 1792, not long after the US founding, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson claimed that the Doctrine of Discovery developed by European states was international law applicable to the new US government as well. In 1823 the US Supreme Court issued its decision in Johnson v. McIntosh. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Marshall held that the Doctrine of Discovery had been an established principle of European law and of English law in effect in Britain’s North American colonies and was also the law of the United States.”

This form of white supremacy ideation further expands within the US as Manifest Destiny and is clearly still present today as Dunbar-Ortiz continues: ”The Doctrine of Discovery is so taken for granted that it is rarely mentioned in historical or legal texts published in the Americas. The UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples, which meets annually for two weeks, devoted its entire 2012 session to the doctrine. Three decades earlier, as Indigenous peoples of the Americas began asserting their presence in the UN human rights system, they had proposed such a conference and study. The World Council of Churches, the Unitarian Universalist Church, the Episcopal Church, and other Protestant religious institutions, responding to demands from Indigenous peoples, have made statements disassociating themselves from the Doctrine of Discovery. The New York Society of Friends (Quakers), in denying the legitimacy of the doctrine, asserted in 2012 that it clearly ‘still has the force of law today’ and is not simply a medieval relic.”

A phrase that I hear in response to my cultural work from non-Native card-carrying democrats who identify as progressives is, “I support Native rights, but I don’t think they should be able to hunt sea otters.” Through my research and lived experience I am starting to conclude it is predominantly the legacy components of the Doctrine of Discovery that manifest in the Pristine Myth and the standing for modern Western conservation moral authority. This emboldens them to say a condescending and demeaning thing without contemplating how that statement contradicts itself, obverting the true power of what they are actually asserting behind those masked words “I support Native rights but…”

Colonial expansion has made a giant city out of the world, turning nature into a theme park with its relentless pursuit of dominion and the final stage of this colonial project is to create a global thermostat to control climate change through geoengineering. The continued capitalist trap is about seeking a technical solution through the same cultural approach that birthed the problem in the first place. Instead of taking time for internal reflection on how their historic cultural roots are continued in how they interact with nature today, this results in the forms of cannibalistic consumption and a savior complex that stems from a self-created delusion in the quest for power.

In “A Yupiaq Worldview,” Angayuqaq Oscar Kawagley states this in gentler macro terms, “A significant difference between Western scientific and Native worldviews is apparent. The Western is formulated to study and analyze objectively learned facts to predict and assert control over the forces of nature, while the Native is oriented toward the synthesis of information gathered from interaction with the natural and spiritual worlds, so as to accommodate and live in harmony with natural principles.”

My art and practice of living our Native ways of life in the present day challenges anti-Native policy, the lingering colonial mindset of divine right to rule America’s original peoples, and the role that mindset has in ecological collapse threatening Indigenous peoples and the natural world we depend on. My work both unintentionally and intentionally discomfits viewers who subscribe to mainstream, non-Indigenous views of conservation, believing that we must “preserve” nature by minimizing human interaction with it. This is in contrast to Indigenous perspectives: We must build reciprocal, intimate relationships with plants and animals, as we nourish ourselves and adorn our bodies with them every day.