national spotlight

For our people, there is a familiar pattern of Indigenous culture being appropriated by outsiders, for example, by slapping designs from Native art onto their products. Although some may believe they are honoring or paying homage to our culture, Indigenous artists may feel used and looked over when their art is co-opted by large brands to promote an agenda or make promises that aren’t kept.

But, pause with me for a moment. It can be easy to focus on the bad actors and miss signs of progress. And when it comes to a constellation of young Alaska Native artists getting their work out into the world on their own terms, I’ve observed a trend-line moving in the right direction.

For our people, there is a familiar pattern of Indigenous culture being appropriated by outsiders, for example, by slapping designs from Native art onto their products. Although some may believe they are honoring or paying homage to our culture, Indigenous artists may feel used and looked over when their art is co-opted by large brands to promote an agenda or make promises that aren’t kept.

But, pause with me for a moment. It can be easy to focus on the bad actors and miss signs of progress. And when it comes to a constellation of young Alaska Native artists getting their work out into the world on their own terms, I’ve observed a trend-line moving in the right direction.

Actually, all of these constituent ingredients —these national works of usable art — are already realities. And I know more are to come. Even as our country grapples with its troubled history and the work left to do, there are simultaneous embers of hope in how our Native cultural works are being appreciated, consumed, compensated, and respected by national organizations, companies, and governments. It’s up to us to stoke those embers into a warming, shining blaze.

In November of 2020, Crystal Worl was one of five Indigenous designers chosen from across the country to design a Wells Fargo credit/debit card. Crystal lives in Juneau and is Tlingit from the Raven moiety, Sockeye Clan, from the Raven House. On her mother’s side, she is Deg Hit’an Athabascan from Fairbanks. The card’s neon pink and blue formline design evokes the theme of balance, which underpins Tlingit kinship and life.

“We’re constantly on the verge of over-extending ourselves,” Rico admitted with pride. “Both of us are very ambitious and have high hopes for our work and what the representation of Native artwork could look like in the future.”

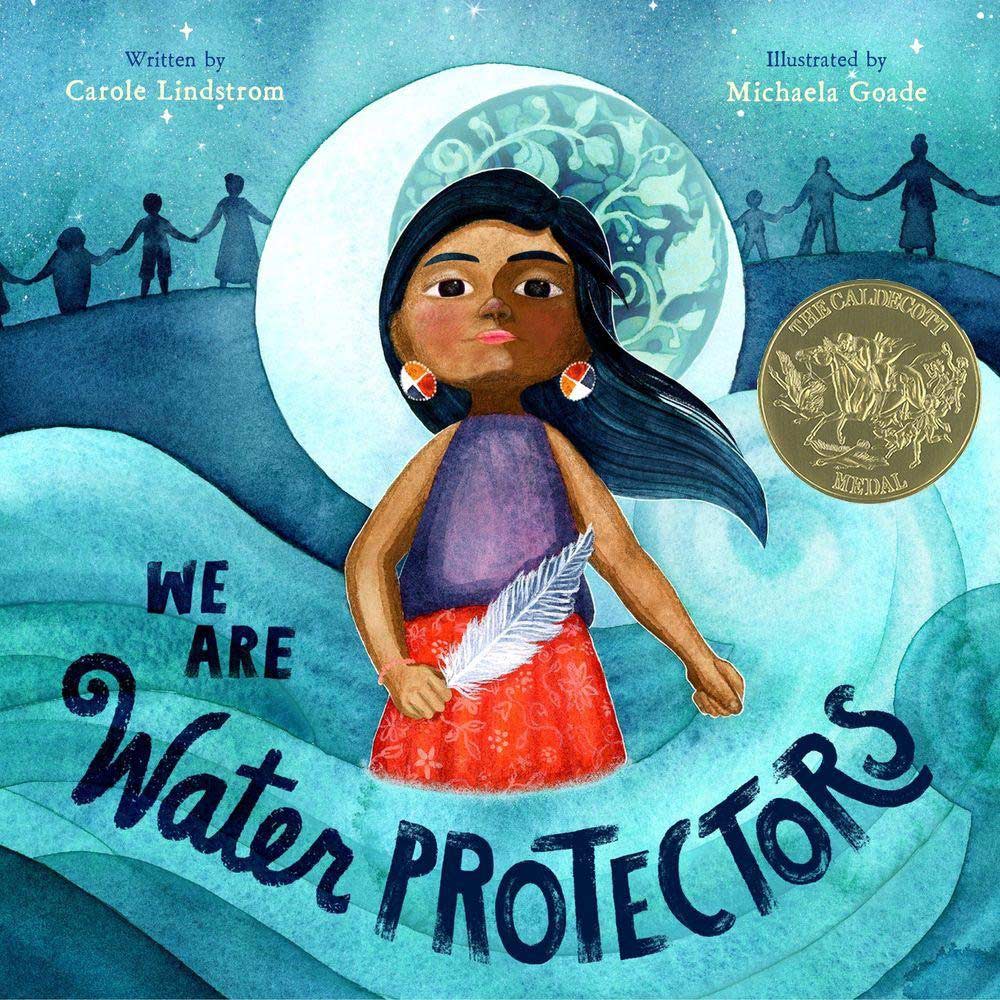

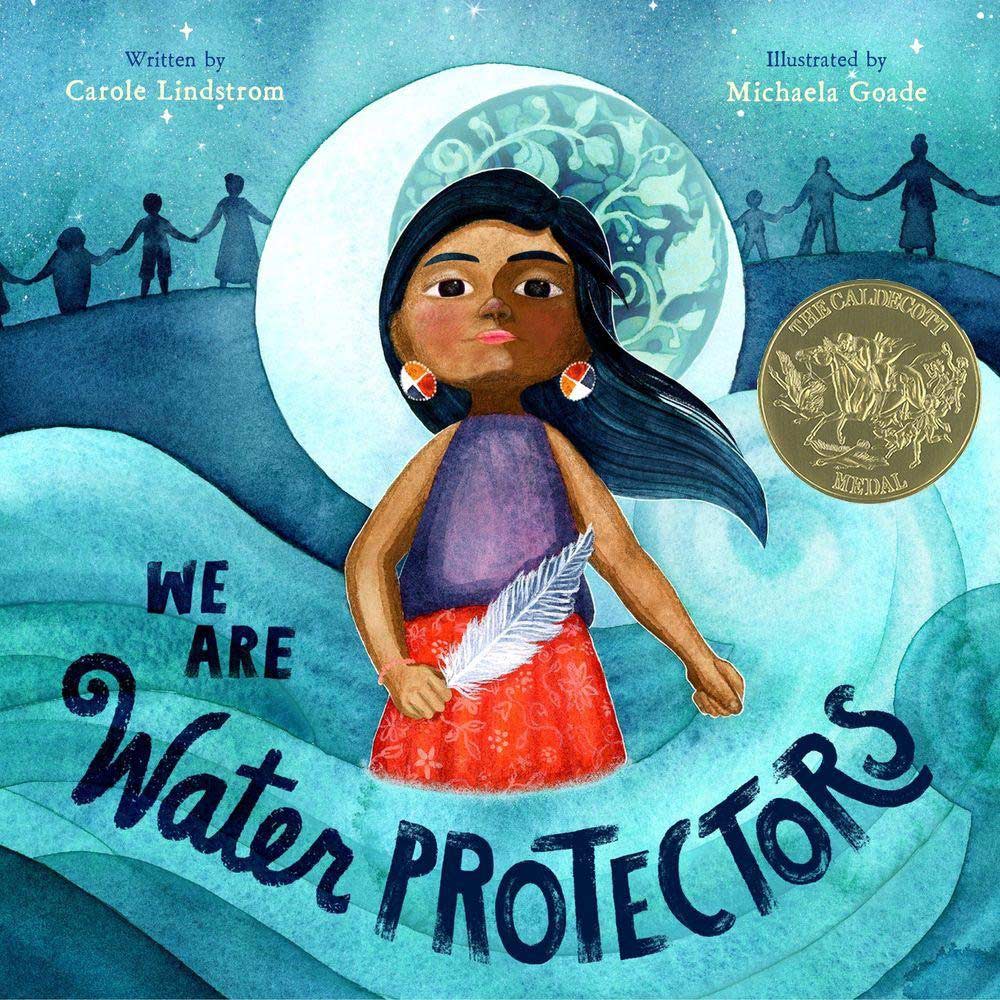

PHOTO COURTESY OF MICHAELA GOADE (TLINGIT)

All three of these artists emphasize that starting with local partners was key to their expansion to a national audience. Goade did a lot of graphic design early on in her career, but wanted “more art in my life, all the time.” Sealaska Heritage Institute’s Baby Raven Reads program, which promotes early-literacy, language development, and school readiness for Native children, helped catapult Goade toward more work in children’s book illustration. One of them was Salmon Boy, which she illustrated, and which won an American Indian Youth Literature Best Picture Book Award in 2018. Goade describes that award as the “first domino that got me into this competitive, national industry.”

While she has a book agent, Google proactively reached out to Goade “out of the blue” last summer to do the Peratrovich Google Doodle. She says Google was looking for Tlingit illustrators and had seen her work with picture books. The company didn’t give her much direction; she was able to let her creativity shine through with watercolor. But it was no small feat. Goade painted separate color layers and textures one by one — the water and sky, fabric of Peratrovich’s shirt, her skin color, etc. — then scanned all of those pieces and collaged them together digitally. The Caldecott award and the Google Doodle were announced just one month apart. “It has been a wonderful and intense month,” Goade reflected at the time.

Though Crystal has been a Wells Fargo customer for years, she took seriously her responsibility to vet the debit card design opportunity just like she would any other project.

“At first, I wasn’t 100 percent on board,” she recalled. “I wanted to do research to find out if I was doing the right thing. Wells Fargo has conflicting histories with Indigenous peoples. I looked at ‘what are they doing now?’ ‘who are they hiring now?’”

She was happy to see they had made progress on several fronts, including dedicating $50 million in recent years to tribal advocacy and community outreach in Native communities. Crystal noted that for Indigenous artists there is often a lot of research required. “I’m not going to blindly walk into an agreement,” she said. “I’ll investigate whether it aligns with my goals, beliefs, ethics, and morals.”

Goade shares those feelings. When she considers illustrating a book, she begins by reading the manuscript and thinking a lot before responding. And not just because of the time required: she can work on a book for two years sometimes. Goade reads up on history and becomes knowledgeable on the subject she’s illustrating, making sure she’s not doing harm. Beyond the world of book publishing, she notes that the ethical calculations get even more complicated, particularly working with large for-profit corporations.

Along with elevating Indigenous art, making longer term and monetary commitments to communities of color is important. As an effort toward this, the Peratrovich Google Doodle was announced alongside a $1.25 million donation that Google.org made to the National Congress of American Indians, the oldest and most representative American Indian and Alaska Native organization serving tribal governments and communities. The funding provided direct cash grants and business training to hundreds of Indigenous-owned small businesses in the U.S. that have been impacted by COVID-19. While $1.25 million is a fraction of Google’s annual profits, it’s a start.

The Black Lives Matter movement and uprising against racial injustice over the last year has demanded that many large companies, governments, and national organizations examine their relationships to creators of color. Goade sees that happening in the publishing industry too, which has traditionally been very white. She’s seen strides in recent years in the industry’s work on inclusivity and diversity, which she hopes continues to grow.

“I’m fortunate to enter the industry now,” she said. “It was different five or 10 years ago. You weren’t seeing this energy to lift up diverse voices…it was common to get publisher pushback, like ‘these stories won’t sell’ or ‘we don’t have a market for this, we’ve already published a Native book.’”

Goade hopes the Caldecott recognition will show publishers that these stories have an audience and need to be elevated.

“There’s a national trend for supporting stories from people of color and letting people from those communities tell them,” Rico said. He points out the release of the 2018 movie Black Panther as a watershed moment. The film was created and largely controlled by Black people, and showcased an inspirational African utopia in the fictional nation of Wakanda. The movie was not only an artistic triumph, but it was a smashing blockbuster success that proved there was an audience hungry for compelling Black cinema. Subsequently, there have been more successes in creators of color telling stories on their own terms, and that art gaining traction in popular culture.

Closer to home, the PBS Kids show Molly of Denali, which features an Alaska Native as its main character, has engaged significantly with Native culture bearers, Elders, writers, and artists along its development, paving the way for new depictions of Native people on screen.

Rico noted, “People and places who are making decisions to feature these stories [from communities of color] are realizing it’s a lot easier to do than previously thought — they go to a community and ask how they want to be represented. It’s exciting.

“At this point in time, any appropriation or art theft is just lazy business and the weakest demonstration of creativity,” Rico continued. “BIPOC [Black, Indigenous and Peoples of Color] artists are putting themselves out there. We’re on Instagram and Facebook, and we’re hustling. We’re available to work with.”

“It’s becoming a trend to not culturally appropriate, and instead work with Indigenous and Black artists to do designs and public art,” Crystal noted. She points out that people across the world seek out Native art because of the powerful stories and designs they’re encoded with.

“[Our art] is visually stunning and beautiful, and the rest of the world values those things,” she stated. “But there are values in our art that are also shared. When we’re collecting materials for weaving a blanket or carving a totem pole, we’re making sure we’re leaving enough for the next generation; being aware of what we keep and take…those are important to be shared with the world.”

When asked what advice she has for other Indigenous artists who aspire to national work, Crystal offered this: “Do your research — take the time to look into what it takes. Be patient with others who haven’t worked with artists before; it’s a learning curve for them, too. And value your time. You spend years mastering a technique; don’t undervalue yourself.”