Setting the stage for the climate battle—on our terms

By ilgavak (Peter Williams) (Yup’ik)

Wilson Justin (Ahtna/Alth’setnay)

dealing with the danger in front of you

dealing with the danger in front of you

Setting the stage for the climate battle—on our terms

By ilgavak (Peter Williams) (Yup’ik)

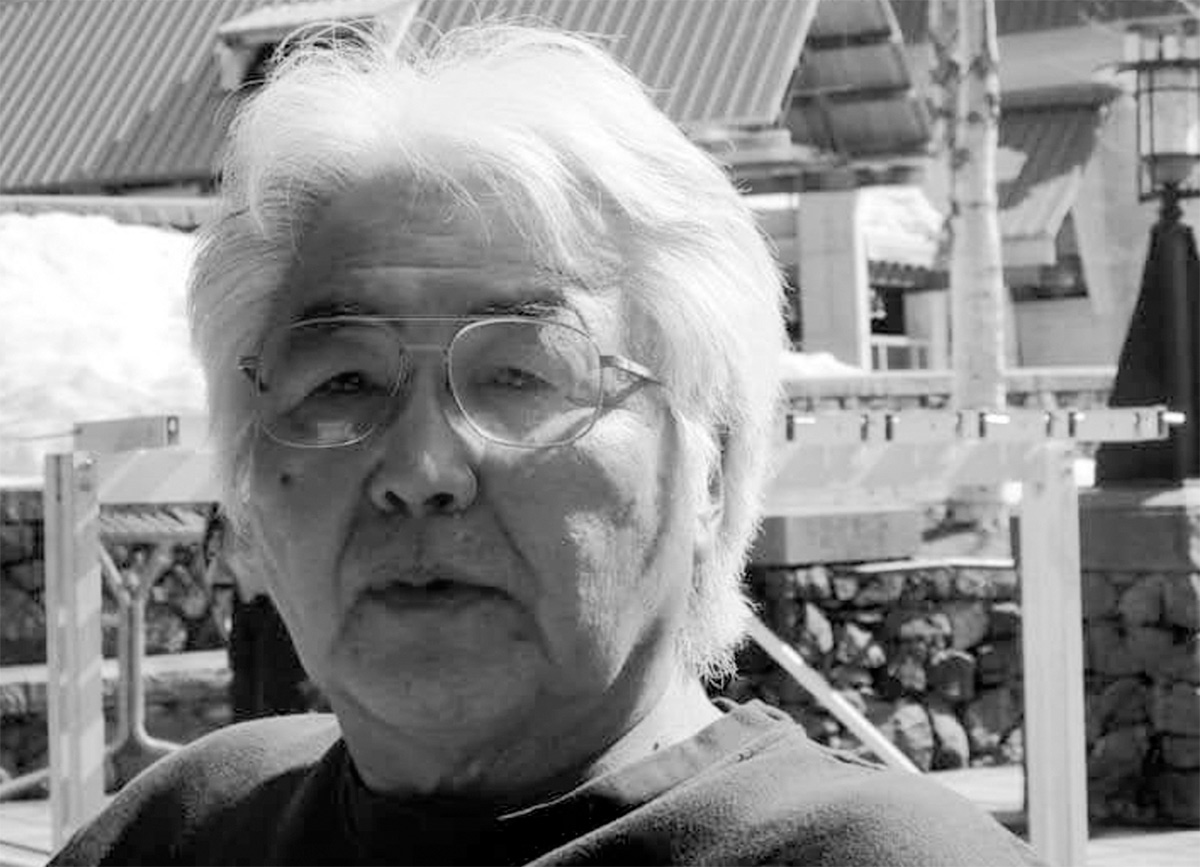

Wilson Justin (Ahtna/Alth’setnay)

There were more than a dozen tents scattered across patches of grass and log cabins. The National Science Foundation had funded the event. In order to have a deeper conversation on the impacts of climate change and its solutions, the Association for Interior Native Educators, PoLAR Partnership, and International Arctic Research Center collaborated on the project. Combining Alaska Native science and perspectives with Western ones. Collaborating on Climate: The Signs of the Land Camp as a Model for Meaningful Learning Between Indigenous Communities and Western Climate Scientists by Malinda Chase (Deg Hit’an Dene’) among others.

Having spent decades researching and learning to observe climate change, as an Elder Justin contributed his cultural expertise to the camp. A flowing white mane of hair with streaks of grey stands out against a sepia complexion, a bright smile, and a twinkle in his eye. These all contribute to his insatiable thirst for wisdom that “was given to me in trust to share. I wasn’t considered a teacher; I was considered a conduit.” His wisdom is accompanied by a playfulness that leads him to tease those who remain uninterested in his teachings. “I pulled their whiskers and burned their noses,” he said, referring to conversations with Western scientists and policymakers that were closed to his cultural lens and truth. With a humorous tone, he recounted his use of words, stories, and concepts to challenge preconceived notions, to combat systemic racism, and at times, to call attention to the denial of the alarming ecological changes he has witnessed and spoken out about.

Justin speaks with the same eloquence you find in great literary works. The cadence in his voice is rooted in the form of being that has been breathing life into cultural traditions and a reflection of a way of knowing that has existed for thousands upon thousands of years. This article focuses on the ancestral power of his words. Justin will speak for himself in this work, as transcribed from the interview, which may seem odd at first. Yet this is also an Alaska Native cultural approach to communication and intergenerational transfer of knowledge.

In taking a long-standing oral tradition fused with modern forms, I realized that the lack of an ancient written alphabet in many Indigenous cultures is often viewed with the subtle racist bias that not having written language comes from a place of deficit. Implying that Native cultures were not advanced or intelligent enough to have developed one and that oral forms of education and history are at a disadvantage. Instead of the benefits that verbal correspondence creates and is informed by a broader cultural context, a deliberate way of interacting with the world.

A profoundly personal relationship-based approach to one of the most important ways we connect, communication. I am not dismissing that writing can come from the heart or that it transforms our lives and reaches out to our souls, for it does. Those same works are painstakingly crafted in isolation where editing, control and quantification produce polished work. Oral communication is breathing, evolving, raw with vulnerability and very much rooted in a present form of communion. Text is frozen in time, while generations and the natural and spiritual worlds are not. I believe our Ancestors understood this. Reciprocity and relationships are foundational values of our culture. It makes sense that how we express ourselves, learn and pass on our culture is grounded in those beliefs.

I first interviewed Justin at the camp along with the help of another participant, Chandre Iqugan Szafran (Inupiaq). I interviewed him again five years later; following are excerpts from both interviews.

the orchestra

After a few years of that, you’re listening 24/7 instead of when something just turns on. When you start listening 24/7, the murmur of the river when it’s gett’n ready to come up or go down mean one thing. The rolling of the rocks in the river is very clear. You can hear it two miles off; the rolling of the rocks means that the river’s coming up. And it’s running very fast. When the river goes quiet, it means that the bottom goes out. There’s no bottom to it at that time; it’s fifteen feet thick there’s three different currents under there. The bottom current is the slowest. The second current is the next slowest; the top current is running fast, so the sound is muffled. No matter how much rocks are moving, rolling around down there, you can’t hear em.

So the river sighs. And then it murmurs, and then it talks and shouts. The birds do the same thing; everything out there is tuned into each other. Birds hear the same thing you do in terms of the river; they know when the rivers gonna change. They know when the streams are gonna change, they can hear a fish in the creek a mile away; I can only hear it fifty yards.

So when you grow up in the atmosphere of being tuned into the forest and the fields, the rivers and the lakes, 24/7, you become so much a part of the existence that you don’t differentiate between yourself as a person, and the river and the field and the mountain. You’re all just part of the same thing; it doesn’t take you long to realize you’re an important part of the orchestra, a song. You’re a part of the whole process of the signing, of the landscape to itself. Eventually, you hear things in a way that you can never explain to people. You’re so tuned in that it is impossible to not be a part of the landscape. The second part of what I was talking about today is that this is an orchestra, birds and everything. So much of the essential part of my grow’n up and so much a part of my being me, the identity, so much a way of spiritual fulfillment. You go to sleep at the end of the day feeling like you’ve danced and been made welcome all day long by these things.

I spent decades in the office doing work…but 2013 is when I really got hammered. I went home and all of these birds that used to be so much a part of my background because of climate change and because of the way the agriculture pesticides were used in the 70s and the 80s. All the friendly crowd that used to be out there cheering, singing, dancing, fluttering, and everything was gone.

It was eerily silent compared to what I grew up with and it was the most lonesome desolate left behind feeling I ever had in my life. It was like somebody just took away the world. The disappearance of all the familiar birds and things and the songs and the orchestra of my youth created this vacuum. Big huge feeling of helplessness that you were left behind. The other thing that the older people said was that “when you walk through the shadows,” very similar to what religious folks like to talk about in the Bible, the valley of death. When you walk through shadows, which is going to happen when you age, remember that even the shadows have a song.

the key is to have a spear; the key here is language

I heard others talk about the saber-toothed tiger. They were referring to a time when we almost met extinction, in the constant face of attacks of the saber-toothed tiger. So we, by attrition, through losing and dying, we learned how to fight, we learned that in the middle of their chest, there is a really heavy bone. That you could not actually kill them the way you would a bear, drop a half of a spear into the ground and anchor it, and let the bear impale themselves on the long copper spear.

You couldn’t do that with a tiger because he was so heavily chested. But on top of his breast bone is his throat, and his throat does not have any covering. So the trick with the saber-toothed tiger – and these are the old stories -was to get a different kind of spear, a longer one. But you wanted the spear to get into the throat, not into the chest, which is a slight tactical change. But when you do that, you could kill the tiger. And you had to make the tiger not charge you but spring towards you. You had to make the tiger go up in the air and come down—enormous bravery for a person to go out there and face certain death.

Walter Charlie, in his last days, was telling me about the saber-tooth tiger and he said, “You young Indians”—and he was talking to me and all my generation—“is gonna have to learn to change the way you use that spear. For the next, for whatever is coming. The way you used that spear in the past isn’t gonna work.” And he said, “You have to sit underneath the tiger. Or you have to sit under the Engii; you can’t run from it. If you run from it, he wins.” So later on, when we were close to being done, he said, “You know your Dad’s people used to talk about two sun. When that happen, when the time come for the two sun, instead of killing each other. Instead of running spears through each other, you have to learn one language. How to deal with this new saber-toothed tiger. You have to reteach yourself the language dealing with this danger. And when you learn how to reteach yourself the language necessary to deal with the danger. You have to come up and deal with the danger directly in front of it.”

So the very clear lesson of facing the enemy that was gonna be in your face without flinching, and using a language that was necessary to communicate with the people in your activity, became very clear to me by early 2000. That the language is absolutely essential in dealing with the next adaptive phase. We are only going to survive if we learn how to speak directly with each other on what needs to be done. We can’t survive by saying, “You’re wrong; the data isn’t supporting your side.” That doesn’t work.

If we put together a language that our grandchildren can understand from when they’re kids all the way up to when they’re adults, we will have given them a spear. The spear that we are metaphorically speaking about that the Elders are telling me is language.

And it’s all different, the sky is, so what the Elders were saying is: change the way you use your spear, your language. Change it to fit the enemy and let’s not worry what is the enemy; there’s always an enemy. Always something, always saber-toothed tigers, there’s always glaciers, there’s always rampaging floods, there’s always something. It doesn’t matter whatcha call it. It doesn’t matter what the enemy is. It only matters that there is going to be one.

The key is to have a spear; the key here is language. As I said today, I have no fear of the future. I have lost this fear of the unknown… I have lost this whole idea that there is something out there terrible that is going to chew me to pieces. Once you lost the terrible grim fear of the unknown all of a sudden, you say, well shucks, how soon can I get a better spear for the next big bad thing. And where are we going to fight this big bad thing? We don’t wanna fight em in his habitat, which is the grass where he’s invisible. We don’t wanna fight him at night where he can see us and we can’t see him. We want to fight him on our terms. So what you’re talking about is in terms of dealin’ with climate change is producing our terms for the battle. That’s reducing the carbon, that’s one. And that’s looking at the issue of changing our energy…reliance on fossil fuels. Those are all setting the stage for the battle on our terms. They are not the battle; they are setting the stage.

It’s all metaphorical, but it’s the best way I can think of to explain how I think about climate change.

catching up: second interview

The key ingredient in all of it is, number one, the model of approach that we have to contend with that is totally absent is that it’s we that have to change first and foremost. And that’s the part that I used where we have to reset our minds and re-engineer our language. So our language, instead of being property driven, protective, defensive and legal in nature of what we had been, to attain the language we have to incorporate into our everyday life now is that it’s us that causes this. Now, what do I do today to stop what is going on? One of the things that you can do is quit spending money on stuff that are play or fun, or creates or adds to the climate change difficulty.

Behind all of this discussion, there is not an Indigenous society in the entire world that has not already spoken to these destructive things hundred years ago, 500 years ago, thousand years ago. It seems Indigenous societies have a built-in, early-warning system to these things. We use medicine people for it, but others use stories; others use what I would call historical retelling of extinction-level events. So every Indigenous society in the world has some way of looking at these extinction-level events and changing the language in themselves to accommodate whatever happens. Only the Euro-Western is incapable of moving there. So the question you have to contend with, in your generation, is how do you get from A to B? So that’s the whole thing in a nutshell. Not climate change, that’s already happened, not the warming of the climate that’s been going on.

Like I said at the start, if ya only hear the songs of the past, then the only song you’ll produce is one of the past. And an orchestra has to be forward, two or three generations, producing songs that the generations way down the road can hear and understand in order to deal with what we did and what we produce in terms of extinction-level events threatening us.

But anyways, the central issue in science, not observation, but actual data-driven science, is the lack of being a participant, and that is a fundamental change from the way Indigenous people think about things. A scientist takes great pleasure in being non-participating, non-involved. Their data is strictly in the hands of Mother Nature. And people like me say, “That’s the problem.” You do it, specifically, in terms of, “Weren’t me. Had to been them other two guys.”

And people like me say, “Exactly the reason why things go haywire.” They don’t like to hear that. Nobody wants to hear that. But in our Indigenous society, you are a part of it all. That’s the universal connectivity that I spoke to at that camp. The orchestra, we all have our instruments, we’re all a part of the orchestra, we all have notes to play, and we all have to sound like we’re together. You can’t be above it and separate. So scientists, in my estimation, have a bad habit of elevating themselves out of the picture… which totally approximates the old-time medicine man taboo about making yourself God. And that is fundamental to, I think, all Indigenous societies when it comes to these discussions. Don’t elevate yourself.

Stop utilizing the idea that we’re above it. That’s the central issue. As long as we think like a lot of the Euro-Western mindset has, “Had to have been those other two guys, weren’t me.” As long as that mindset is in place, we can’t stop using fossil fuels and being a contributor. And that’s been my central question, move that camp out of the discussion and into, “I will no longer be above it all, and I will accept responsibility for what I’ve done.” It’s an amazingly simple equation, but two generations of trying to look at the idea of how do you stop being the center of the universe to an entitled population? That’s pretty tough.

What was being said was that, first, we’re going to self-medicate, whether you self-medicate with ignorance or pain pills, or opioid or heroin. Makes no difference; self medication is the key. In other words, put yourself into some kind’a La La Land where it doesn’t matter what goes on out there. And it’s the same thing that you deal with in terms of the academic approach where you use words. If you look at some of the research articles that I’ve had to contend with in the past 30 years, especially from the ‘90s, where you have 10,000 words, that has almost no bearing and meaning in your everyday life, for a particular topic that I could do in three pages. You tell yourself, these guys are feeding themselves heroin with English language to self-medicate. They aren’t explaining anything. They aren’t talking to anyone.

So what we’re doing is self-medication. But eventually, you have to stop the addiction. And that’s where people like me step in and say you don’t stop addiction until you take yourself out of the equation in terms of being above it all. When you have scientist A and intellectual B, and government agency representative, three, all speaking in terms of themselves being above the issue at any given time, whether it’s community planning, medical crisis, like the pandemic, as long as they have the ability to speak in terms of being separate and above the problem, you’re going to have a problem. So basically, what we, you and your generation, me and my generation, have to do is speak to the problem of us being addicted to ourselves, then we can look at change. So that’s the basic issue. When you use plain English, it becomes very clear what the problem is.

I grew up in a very hostile environment. If I wasn’t tough and mean, I wouldn’t survive. But on the other hand, eventually, you have to put your anger in context to say it’s a shield. You only need shields if you’re in the middle of an enemy camp, and then comes the next question, what the heck are you doing in the middle of an enemy camp? You’re supposed to be among friends. So you learn how to make friends, and once you learn how to make friends who become, what I would call, a positive addition to somebody else’s life, whether it’s kids or the next generation, or yourself. Once you learn to do that, you don’t need that anger as a shield all the time. So you learn where and when to put the shield down, but you can’t learn to put the shield down until you become a positive force in somebody else’s life. And if you don’t do that, you’re always stuck with me, myself and I. Me, myself and I is exactly why we’re here today.

acceleration of change

Wilson has spent decades observing and trying to understand what his Elders were teaching, so he can hand down that gift of knowledge. When Chandre and I interviewed him five years ago, he laughed while explaining how confused he was in deciphering their words as a young man. I can relate; Wilson felt that it was necessary to mention this as a footnote. “We don’t want our youths to think they are the only ones to have difficulty with a language that knows only how to take as opposed to gifting or sharing. It is immensely difficult to take a value-based language steeped in time. And convert it into a written form that’s based in a property language without losing its original meaning.”