Organizing

Up North

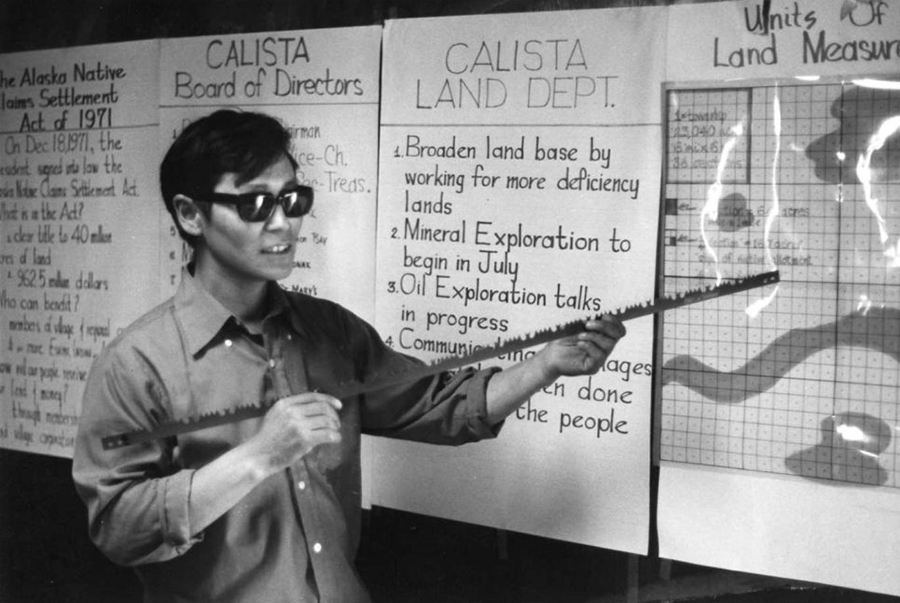

his year is the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA,) which has changed and benefited all Alaskans in fundamental way. Passed in 1971, the act provided a cash payment and settlement of outstanding claims of Alaska Native people over lands they never ceded to the United States and continued to use for hunting, fishing and other ways of life.

ANCSA’s impact, however, went beyond the cash settlement and the land. It is also linked with the creation of two large regional municipalities, or boroughs, in Alaska—the North Slope Borough in 1972 and Northwest Arctic Borough in 1986.

Those two municipalities, the largest in the U.S by land area, took advantage of the natural resources in their areas, oil for the North Slope and minerals for Northwest Arctic, to bring back self-governance and to revolutionize the lives of people in their areas.

“For a long time, after white people came to Alaska, the Native people had no role in government,” said Willie Hensley (Inupiaq), who was deeply involved in the struggle to get Alaska Native land claims settled. Even Alaska’s constitutional convention was all white, except for Frank Peratrovich (Tlingit), from Southeast, Hensley noted.

The settlement of land claims and the creation of these local governments, at least the North Slope Borough (the Northwest Arctic Borough came later) happened almost simultaneously and they were interconnected.

Had ANSCA not happened when it did, settling the Native land claims and allowing the Trans Alaska Pipeline and North Slope oil fields to be built, there would no tax base to support the new borough, and no revenues to support public services and schools. There was a more direct link in the Northwest Arctic Borough where NANA Regional Corp. was able to select mineral lands where the Red Dog Mine, the world’s largest zinc mine, would be built. As with oil on the North Slope, the development provided the money for schools and other services and helped make self-governance possible.

a long and difficult road

The pressure on Alaska Natives was increasing. In many areas, Natives were already traveling long distances to hunt game and to fish. Those resources, though available, were spread over large areas and the land conveyances to other entities under the Statehood Act meant opened the possibility of having to skirt lands owned by others and travel even longer distances to get the game or fish.

In the early 1960s, Alaska Natives began to file claims on lands needed to sustain them. They also formed organizations to press their claims. North Slope leaders—Charles Edwardsen, Jr. (Inupiaq), Guy Okakok, Sr. (Inupiaq), and Samuel Simmonds (Inupiaq)—organized the Arctic Slope Native Association (ASNA) in 1965 and filed claim to 58 million acres for the Inupiat. ASNA’s first executive director was Eben Hopson (Inupiaq), who later became the first mayor of the North Slope Borough when it came into existence in 1972.

In 1968 the huge Prudhoe Bay oil discovery on lands previously transferred to the state provided further impetus to settle the claims. The desire of oil companies to move that oil to market also played into the settlement when it became clear that pipeline construction required a resolution of Native claims to secure a right-of-way.

The route of the proposed pipeline traversed lands claimed by several Native groups. The state and the oil companies now realized that the pipeline, a future source of great revenue to the state and profit for the companies, could not be built until a resolution of the claims was achieved. The oil companies and the state now joined the Native associations urging Congress to reach a settlement.

Meanwhile, congressional leaders in Washington, D.C. were worried about the nation’s increasing reliance on oil imported from the Middle East. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Counties, or OPEC, was flexing its muscle (an embargo on exports of oil to the West would come in 1974).

FINDING A FORMULA

One leading idea was a formula based on the population of different regions, and that created tensions between regional Alaska Native groups. North Slope people, through ASNA, wanted land allocated on the basis of what each Native group lost to entities like the state and federal governments.

ASNA held out for a larger settlement of land such as what they asked for in their 1965 filing. They didn’t get it. In the end, ASNA accepted the terms of ANCSA that gave 12 different Alaska Native regions rights to select land from 44 million acres and a cash settlement of nearly $1 billion.

When Native regions voted to accept the claims act, ASNA cast the lone negative vote, knowing that the final land allocation would not give it the 50 million acres it sought. Joe Upicksoun and Charles Edwardsen, Jr. also wrote to President Richard Nixon asking him to veto the act, but Nixon signed it on Dec. 18, 1971.

The next year North Slope Inupiaq formed the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation (ASRC). The corporation received $36 million and the right to choose 5.6 million acres in its region outside of land already conveyed to the state or federal withdrawals made for the National Petroleum Reserve-A and the Arctic National Wildlife Range (which become a wildlife refuge in 1980).

If the ANCSA land allocation were strictly based on population, ASRC’s share would have been much less because the North Slope’s population was small. But Willie Hensley said that a special formula of “land-loss” allowed the acreage to be larger. The “land-loss” formula took into account the dispersal of animals across a vast range, Willie recalled.

But the leaders of the North Slope, feeling stung by not getting more land, were already figuring another avenue to help their people. Even before the signing of ANCSA, Eben Hopson and others were thinking of other ways to empower their people. One idea was forming a regional local government, a borough. The presence of oil and gas and the associated infrastructure provided a base to generate revenue through property taxes.

In June 1971, six months before ANCSA, North Slope leaders filed a petition with the state to create the North Slope Borough. The state approved the petition for the borough in June 1972, and the voters from Arctic Slope villages voted to create the new municipality.

borough supports education

In 1974, the North Slope Borough went on to become a home-rule municipality, which has all legislative powers not prohibited by state law. The borough had wide powers and a few years later it added the power to issue permits for oil and gas development.

North Slope leaders who worked on the formation of the borough knew the importance of schools. Formal education came in the late 1800s when the Presbyterians constructed the first school in Utqiaġvik (formerly Barrow). The federal government took over education from the church in 1894 and in the 1930s put it under the Bureau of Indian Affairs. That Western education failed to take into account Inupiat culture and traditional ways of life. Also, there was no schooling higher than elementary.

Many of the borough’s leaders had gone away to boarding schools in other parts of Alaska or in other states. They knew that local schools would ensure adherence to local traditions, language, and culture. As a home-rule municipality the North Slope Borough possessed the resources to build schools in each of its eight villages, and it did so, including high school.

Several years later Hopson and others, frustrated at the inability of the University of Alaska to provide post-secondary education on the North Slope, formed Ilisagvik College to do that. Today Ilisagvik is thriving, specializing in career and technical courses, and is now organized as a tribal college but still supported mainly by the borough.

ASRC, the new regional corporation, also acknowledged the importance of education. By 1977 the corporation had created the Arctic Education Foundation to provide scholarships and other educational assistance to its shareholders.

CHANGING LIVES

When a local bush pilot noticed discoloration on mountainsides in the DeLong Mountains 90 miles north of Kotzebue, federal geologists investigation and found a mineralized area rich in zinc and lead. ANCSA had just passed and NANA Regional Corp. was selecting lands from its land entitlement. Realizing the potential value of the minerals NANA selected the lands in a race with mining companies who wanted to stake their claims.

NANA prevailed in getting the land and the Red Dog Mine built in the 1980s in a partnership between NANA and Cominco, Ltd., a mining company. It became the world’s largest zinc mine, creating the revenues that allowed the new Northwest Arctic Borough to build schools and to provide other services.

Also, under the 7(i) revenue-sharing provisions of ANSCA, NANA shares 70 percent of the mine net revenues with other Native regional and village corporations. These have totaled over $1 billion since Red Dog went into production in 1989. (ASRC has also made a contribution through sharing of revenues it has received from oil production on North Slope lands it was able to select.)

Both boroughs and their associated corporations changed lives for the residents of their areas. The formation of the two municipalities in the north is not dissimilar to the settlement of the Native land claims, Hensley said. “The foresight of the Inupiaq leaders brought benefits for the people in north. They built houses, provided water and sewer, heat, and healthcare. And we got control over education.”