Hearing on Boarding Schools Wraps Up with Healing Totem Pole Raising

WARNING: This story contains disturbing details about residential and boarding schools. If you are in crisis, here is a resource list for trauma responses from the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition in the U.S. In Canada, the National Indian Residential School Crisis Hotline can be reached at 1-866-925-4419.

People carry the Boarding School Healing Totem Pole to later raise it at the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage, Alaska. Oct. 22, 2023.

People carry the Boarding School Healing Totem Pole to later raise it at the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage, Alaska. Oct. 22, 2023.

Hearing on Boarding Schools Wraps Up with Healing Totem Pole Raising

WARNING: This story contains disturbing details about residential and boarding schools. If you are in crisis, here is a resource list for trauma responses from the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition in the U.S. In Canada, the National Indian Residential School Crisis Hotline can be reached at 1-866-925-4419.

day that had a sad, painful start ended with a celebration of the raising of a Boarding School Healing Totem Pole.

U.S. Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland, Laguna Pueblo, held a hearing on boarding schools on the morning and afternoon of Sunday, Oct. 22 at the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage. Like her prior stops in the Lower 48, devastating stories and painful memories were shared with the secretary.

Anchorage is the 10th stop on the Interior department’s Road to Healing, which is part of an initiative on boarding schools. It’s a year-long tour across the country to hear from Indigenous survivors of the boarding school system and their descendants about their experiences. That sharing is healing, and will contribute to a permanent oral history, Haaland told about a hundred people.

“In Alaska alone, there were 21 boarding schools leaving intergenerational impacts that persist in the communities represented here today. It’s my department’s duty to address the shared trauma that so many of us carry,” she said.

“I want you all to know that I’m with you on this journey. I will listen. I will grieve with you. I will weep, and I will feel your pain as we mourn what we have lost. Please know that we still have so much to gain. The healing that can help our communities will not be done overnight, but it will be done,” Haaland said.

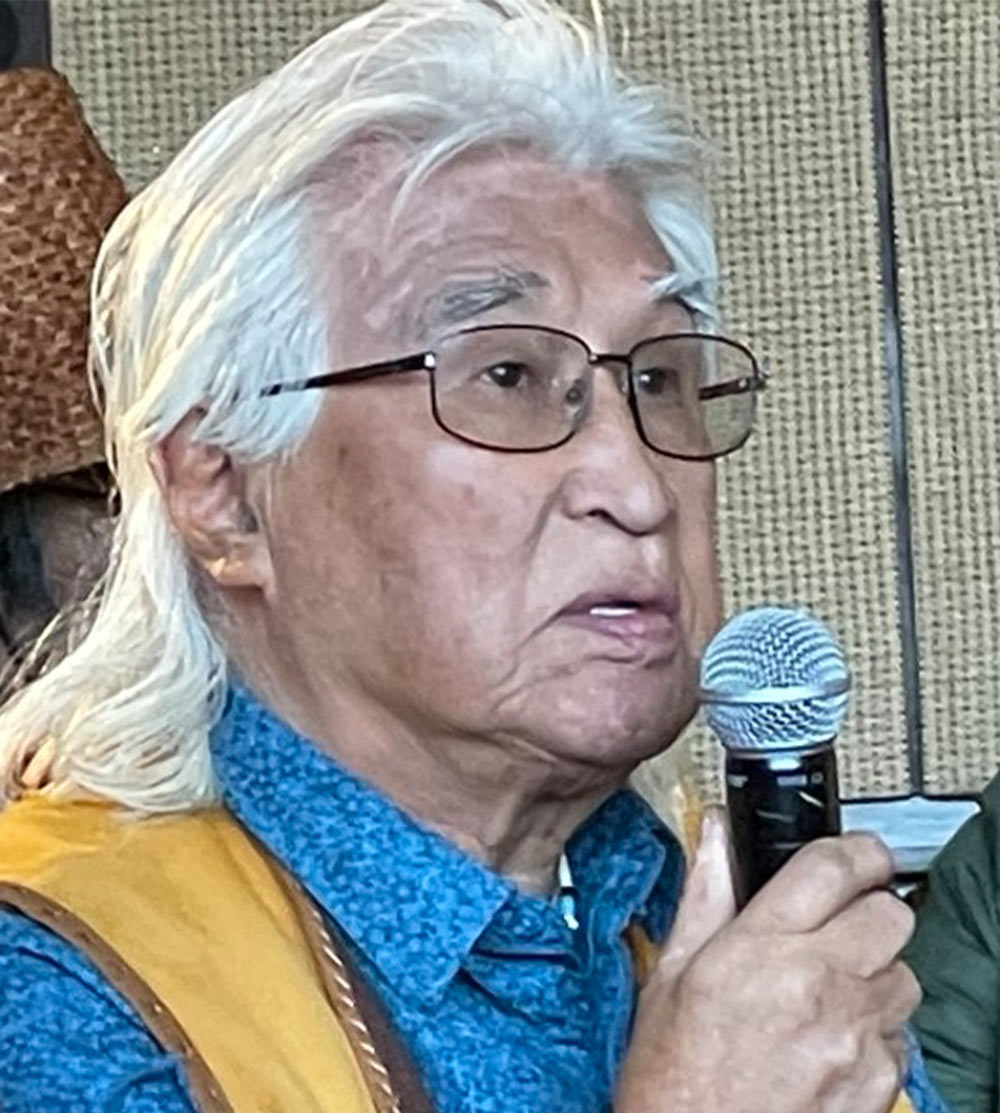

Jim LaBelle Sr. (Inupiaq), president of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, attended Wrangell Institute, which was located in southeast Alaska, and operated from 1932-1975.

Speaking toward Haaland and Interior Assistant Secretary Bryan Newland, Bay Mills Ojibwe, he said, “I saw so many of my fellow students become beaten in so many different ways during our stay at Wrangell for those six years—every conceivable way that one could get punished, many of us experienced,” LaBelle said. He was a resident of the school from 1955 to 1961.

Punishment included “getting our mouth washed out with lye soap, being forced to strip and having a water hose placed on us, on our bodies inside the shower rooms,” LaBelle said.

“We had to run the gauntlet. We had to again be completely naked as our fellow students and kids were forced to use their belts on our naked bodies as those of us who ran up and down the gauntlet. And many times we just didn’t do it once. We did it many times and a lot of times that drew blood on our bodies,” he said.

Fred John, Ahtna Athabascan, who also went to Wrangell Institute, remembers when a group of kids arrived from the Nunamiut Iñupiat village of Anaktuvuk Pass. “They had all their (fur) parkas, their caribou pants. I mean they were dressed. I remember coming in and I was so, so impressed about how beautiful they were.

Detail of the Boarding School Healing Totem Pole, carved by Joe and T.J. Young, Haida. The lower portion of the pole represents a bear holding on to her cubs. Next comes a raven transforming into a human, with a male figure nestled beneath it and two children above it.

Robin Sherry, Athabascan, said nights in the dorm at Wrangell Institute were hard. “Every night you could just hear crying. First, it’d just start really slow. Then pretty soon you could hear the whole dorm crying, girls saying they wanted to go home.”

Her brother and some male cousins from her home village were at Wrangell Institute when she was there. Sherry said, one day a cousin came to say, ‘We’re going to run away [to Minto, in Interior Alaska]…and when we get home, we’ll send for you.’… we waved to them, they waved to us and we were just really happy…Well, they didn’t know the school was on [an] island.”

Sherry said she suppressed memories and almost forgot the year she spent at the Institute. Sharp painful memories hit her, though, when she realized her son was the same age she’d been when she was sent away. Then, a cousin told her about a healing ceremony that was going to be held in Wrangell.

“I’m so glad I went on that trip because it made me realize, ‘hey, I could tell my story. I could share. I don’t have to be ashamed, I don’t have to feel guilt’…I’m just glad I found that peace in my own heart,” Sherry said.

Not all who attended boarding schools have painful memories.

Richard Chalyeesh Peterson, president of the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, said he went to the optional public Mt. Edgecumbe boarding school, which was “probably one of the best times of my life.”

However, he said, boarding school trauma impacted his mother. “My mom today is dealing with head trauma that she suffered as a child at the hands of her own mother because her mother received that same treatment at the Wrangell Institute. Sorry [he apologized for being tearful]. I’m trying to be a better son today than I was growing up when I didn’t understand my mother and the abuse that she endured because her mother didn’t know how to be a mother.”

Haaland and Newland heard hours of painful, emotional testimony about other boarding school experiences. Then, after a break, a celebration began for the raising of the Boarding School Healing Totem Pole and a Dena’ina-Haida potlatch.

“So for those of you who shared your story, I want you to know that we’re keeping it alive and we’re passing it on to our generations and you won’t be forgotten. And that all of that strength and resiliency is living inside of us, and all these beautiful children running around are carrying all of that beauty, all of that strength and all of that healing,” Apok said.

Peterson said Native people are scarred by the impacts of boarding schools and colonization. “But I always say for every problem that with our people, we, our people are the solution. And doing these things, using our culture to erect a totem pole here in Anchorage, that’s healing to our people. Taking those hard topics and discussions of boarding schools and the abuse that happen, the loss of our languages, pulling that out of the dark and putting it into the light so that we can have those conversations is truly what’s needed. It’s truly what’s going to happen to be healing for our people.”

He went on to thank Haaland and Newland, “who are here hearing those heartfelt stories and for the first time ever, not just hearing, but they have that lived experience as well, we can look across for the first time in the highest offices and see our own people. So I’m really incredibly grateful for them.”

Gifts, including blankets and shawls, jewelry, healing salve and other small items, were handed out to people who helped make the totem raising and dinner come about. People enjoyed a meal with curried salmon, salmon chowder, moose stew, baked salmon, herring eggs, shrimp, macaroni salad, and much more plus a mix of berries, sugar and fat, (called aguduk), and pumpkin pie for dessert.