or many Alaskans, our feelings for what our state means to us are as vast as the 375 million acres of land of which it is comprised. How do we begin to describe what is wordlessly amazing about the land and waterways we travel and people we experience? What is that feeling when we step into clear view and see a vista so beautiful, it seems unreal and out of this world? The thing is, it can’t be quantified into a single feeling. The feeling is the abundance of feelings. To what extent would we go to make sure this abundance of feelings is preserved and shared with as many humans as possible for the betterment of life on earth?

This is the question posed to us in Mark Titus’s film The Wild when he asks, “How do you save what you love?”

In this case, he is referring to roughly 27.5 million acres of feelings that make up the Bristol Bay region in Alaska. More specifically, the 12.5 million acres of feelings set aside for development by the Bureau of Land Management, known as the Bristol Bay Area Management Plan. Even more specifically, it’s the 98,000 acres of feelings that have been proposed for development of the largest open-pit gold and copper mine in the entire world—known globally as Pebble Mine.

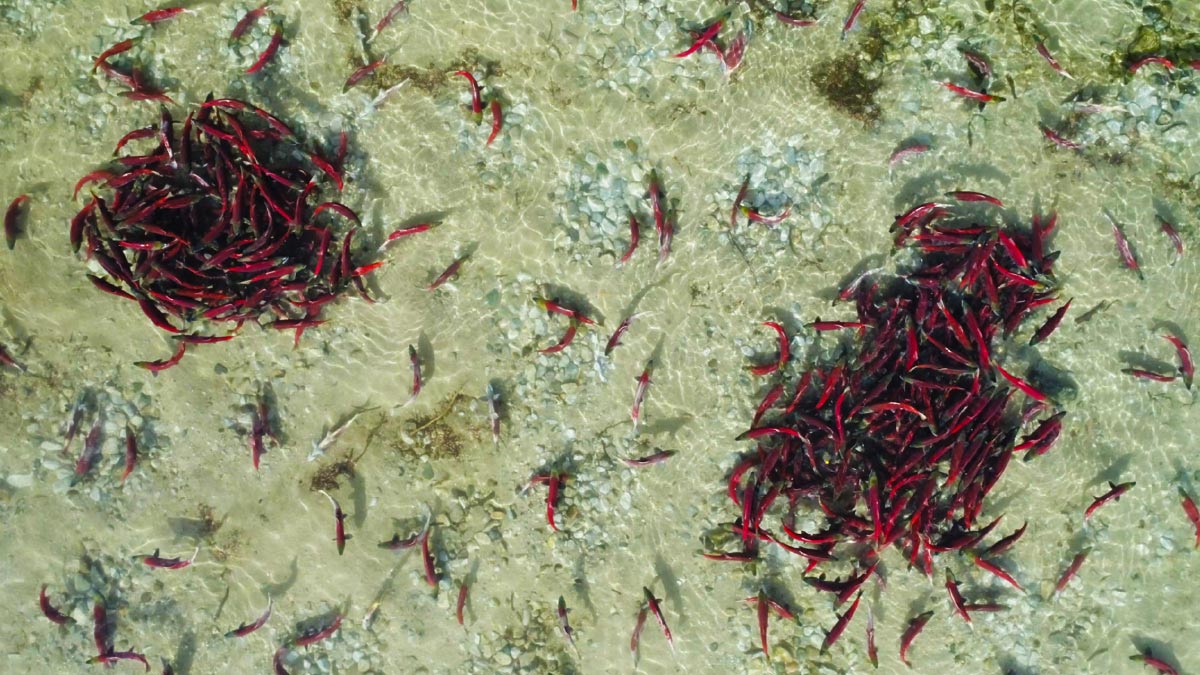

We’ve yet to include the animals that add to the vistas and the indescribable sensations we experience through the combination of all factors and beings within the environment of this space we call Bristol Bay. Have we yet lived if we haven’t seen 100,000 salmon swimming up river toward their glacial spawning grounds? Have we yet lived if we haven’t seen a caribou herd travel across the tundra? Have we yet lived if we haven’t seen the geese migrate home? Have we yet lived if our children haven’t tasted the hard work of gathering food? Have we yet lived if we haven’t passed on the knowledge of how to gather wild food and talk to the wild animals, as our Ancestors have for millennia? This world in which we live is magical in a way we must feel to understand.

Now, how do WE save what WE love?

When we remove ourselves from the text, we realize that political process is really a meek attempt to organize and control what ultimately can’t begin to be contextualized through words alone. It claims to have a plan to ethically disrupt a system of beings in a way that won’t send a snowball into a spiraling weight downhill, eventually aggravating an avalanche of destruction.

But, this would be the largest open-pit mine in the world. How could it not negatively impact the environment?

The Wild was scheduled to kick off its cross-country tour this summer, which would include theater screenings of the film, in-person panel discussions, a food truck with samples of Bristol Bay salmon, and a virtual reality experience to give viewers a taste of life on a commercial salmon fishing boat.

The Wild tour has created a new way to reach people. And, it’s working. “Save what you love” is a concept to which we can all relate, and Tribes, fishermen, chefs, educators, theater leaders, celebrities, activists, legislators, scientists, outdoor enthusiasts and others across the world have rallied around this effort. The Wild has partnered with theaters across the U.S. and has been shown live during virtual events throughout the summer. These screenings are followed by live online video chats with the celebrities and other luminaries from the film. Participants can also order and receive virtual reality goggles and Bristol Bay salmon to sample in their own homes.

Here’s how you can get involved:

Buy a ticket. Tickets for each virtual-gathering cost $12. Each ticket purchase supports local theatre groups during this unprecedented time of financial hardship. Two dollars from each ticket will go directly to help the people working on the front lines to save Bristol Bay.

Connect. Sign up, and get access to the most up-to-date information and calls to action in the fight to save Bristol Bay salmon.

Vote with your dollar. Eva’s Wild (“Eva’s” is “save” spelled backward) is an impact brand donating a share of every transaction back to Bristol Bay. Purchase of Eva’s Wild products directly helps the effort to save Bristol Bay salmon.

Eat wild. We don’t have to tell this to Alaskans. But, encourage your friends in other places to vote with their dollars by purchasing wild Bristol Bay sockeye salmon. This supports our local economy, and it also creates a demand for this food supply.

Call your legislators. Call them, write them, email them – all of them! Tell them you do not want the Pebble Mine in Bristol Bay.

Talk to your friends. Many people don’t even realize this mine project is still in the works. Make sure they understand what is at stake, and what they can do to help.

Visit www.evaswild.com for information and to learn more.

As an Indigenous person who lives to normalize the traditional way of life, hunting and gathering foods from the land, and interacting with mother earth on a daily basis, this also means Pebble Mine will negatively impact me and all beings within this area, forever. From an Indigenous perspective, beings include everything from rocks and grass, to water and air, to mosquitoes and moose, and, of course, humans.

How does it make us feel that living beings are not enough reason to halt a mining operation that would negatively alter thousands of acres of life forever? How is it that the lives and cultures of Bristol Bay can be disregarded, with the stipulation of financial profits? It’s a sad reality we must face.

Economically speaking, hurting humans, water, plants, and animals is not enough reason to stop a development that could generate financial profits. Since we aren’t important enough, here are some things corporate America should pause to consider:

- the Bristol Bay salmon fishery is a $1.8 billion industry;

- it provides thousands of jobs to a local and global workforce;

- these salmon feed 46% of the world’s salmon consumption;

- this food is perfectly safe, sustainable and profitable; and

- it’s the last fully intact wild salmon run in the world.

Bristol Bay fishing fleet. photo by chris miller.

Filmmaker Mark Titus. photo courtesy of mark titus.

Sockeye salmon. photo by jason ching.

Preparing salmon for smoking. photo by mark titus.

Bristol Bay fishing fleet. photo by chris miller.

Preparing salmon for smoking. photo by mark titus.

Sockeye salmon. photo by jason ching.

Filmmaker Mark Titus. photo courtesy of mark titus.

We must say no to Pebble Mine.

As we grapple with the reality of a global pandemic, and the world struggles through COVID-19 and non-essential work closures, one of the hardest truths we have faced is the accountability of our wasteful way of living in the United States. While we are locked down contemplating our options and reevaluating what we can and can’t live without, we see that food will always be the most valuable resource for the majority of people in the lower income brackets of America. The majority of our people are demanding to go back to work so they can pay for food and shelter. Meanwhile, the Pebble project approvals are being pushed through under this blanket of chaos by the Army Corps of Engineers. While the average American is searching for ways to put food on the table, our elected officials are streamlining the permits for Pebble. All for a project that was already considered null under the past administration based on the scientific facts that it was too destructive to the current infrastructure in Bristol Bay to bring benefit in a justifiable way.

Right now, we have a common ground with the rest of the world. In Bristol Bay, we are fighting Pebble Mine to keep our food and shelter intact. We are fighting to feed the world while we feed ourselves. We are fighting to value a sustainable way of life over the stock market. We are fighting to share our Indigenous values as Yup’ik, Dena’ina and Alutiiq people. Life is worth living and fighting for when we protect centuries of traditions and enable them to continue into our modern society.

How do we win this fight to save what we love? We do it by coming to terms with the destruction for which we are responsible and being accountable for the results of our thoughtlessness. We find unity in the ways we are all connected so we can understand what the world has to lose by recklessly developing the incredible 98,000 acres of feelings that are gained through experiencing Bristol Bay. We save what we love by sharing what we have and the trickling effect of gratitude and sustainable benefits that spread throughout the world by valuing life and food over money.

I am Apay’uq Moore, and I chose to be a part of The Wild project because it will take people from all walks of life and perspectives to stop Pebble Mine. Mark and I both love the wilderness, wild salmon, and the people of Bristol Bay. We ask you to join this journey, and take action to save what you love, as well.