Chairman

Sam Kito, Jr. (Tlingit)

Vice Chairman

Valerie Davidson (Yup’ik)

Secretary/Treasurer

Sven Haakanson, Jr. (Sugpiaq)

Albert Kookesh (Tlingit)

Sylvia Lange (Aleut/Tlingit)

Oliver Leavitt (Iñupiaq)

Georgianna Lincoln (Athabascan)

Morris Thompson (Athabascan)

In Memoriam

To the family of Byron I. Mallott, we extend our love and condolences to you.

(Haida/Tlingit/Ahtna)

Alaska Native Policy Center Director

Karla Gatgyedm Hana’ax Booth (Ts’msyen)

Indigenous Leadership Continuum Director

Melissa Silugngataanit’sqaq Borton (Sugpiaq), Indigenous Advancement Director

Eliabeth Uyuruciaq David (Yup’ik)

Financial Director

Angela Łot’oydaatlno Gonzalez

(Koyukon Athabascan)

Indigenous Communications Manager

Kacey Qunmiġu Hopson (Iñupiaq)

Indigenous Knowledge Advocate

Indigenous Advancement Manager

Elizabeth La quen naáy / Kat Saas

Medicine Crow (Tlingit/Haida)

President/CEO

Abra Nuŋasuk Patkotak (Iñupiaq), Special Assistant to the President/CEO

Ella Sassuuk Tonuchuk (Yup’ik)

Indigenous Leadership Continuum Coordinator

Ayyu Qassataq (Iñupiaq)

Vice President

& Indigenous Operatons Director

Anchorage, AK 99501

advertising@firstalaskans.org

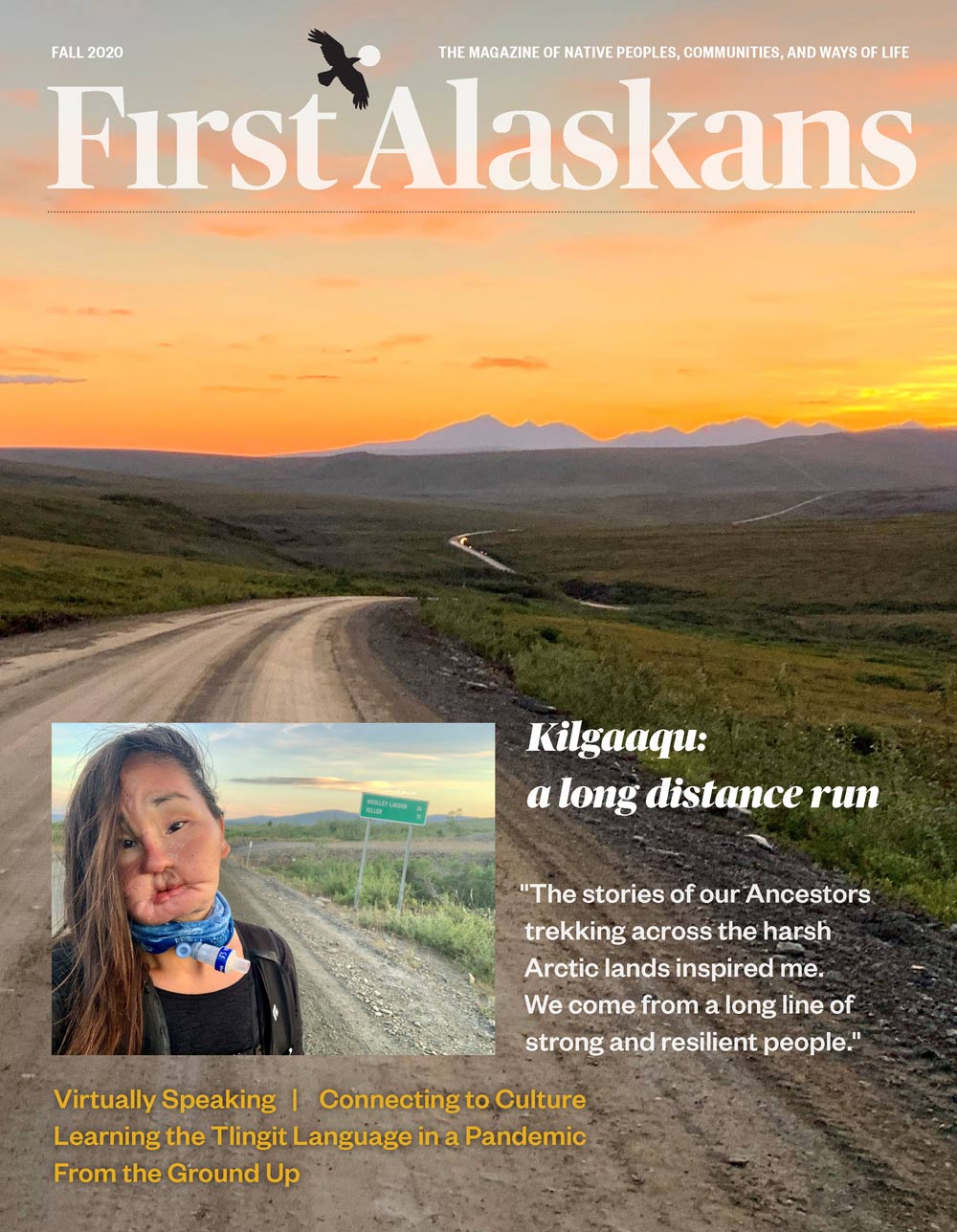

First Alaskans Magazine is published by

First Alaskans Institute. © 2020.

(Tlingit/Dena’ina Athabascan)

Penny Gage (Tlingit)

Leona Long

Carol Seppilu (Siberian Yupik)

Apay’uq Moore (Yup’ik)

Matt Carle (Haida)

Samuel Johns (Gwich’in/Ahtna)

hen Annette Erickson first put up a fence on their Unalakleet property, there was a bit of a stir in the village.

“You’re putting a barrier up between yourself and the community,” said Annette. “People aren’t used to fences here.”

While the local Native corporation had initially approved the fence, they formed another meeting after the community response. So why was a fence so important to Annette? Simply to encourage a healthy food garden.

“We explained that we wanted to inspire people and see what we can do with 6,800 square feet next to our house,” said Annette. “Maybe even help feed our community and answer questions.”

We don’t need to live in fear. Just as our Ancestors have done for thousands of years, we will learn to adapt with a changing environment to keep our people strong.

medium for telling Native stories

lexis Sallee (Iñupiaq), who is also Mexican American, is the host of Indigefi, a weekly one-hour radio show featuring Indigenous music that includes emerging and popular artists and music. More recently Alexis has ventured into a new podcasting media endeavor. In May, her podcast “Native Artists by Indigefi” premiered.

Alexis grew up in Anchorage and joined KNBA after graduating high school. While at KNBA she worked as a sound editor for the radio program, Earthsongs for two years. While there she worked alongside Shyanne Beatty (Athabascan), a local radio personality, learning about the technical aspects of producing radio.

Shyanne worked with KNBA for more than seven years as the Network Manager for Native Voice One (NV1) which distributes Native radio programming nationwide. The experience for Alexis had an influential impression, urging her to learn more about the radio business.

Elders and Youth Conference

pproximately 1,100 people registered for 37th Annual First Alaskans Elders and Youth Conference from Oct. 11-14. The virtual conference was the first of its kind, and hundreds of participants attended daily from all over Alaska and the world.

Dr. Rev. Traditional Chief Trimble Gilbert (Gwich’in) from Vashrąįį K’ǫǫ (Arctic Village) was the Elder Keynote speaker and Kiley Kanat’s Burton (Eyak/Aleut/Iñupiaq/Koyukon) was the Youth Keynote speaker, while Conference Guides were Dustin Unignax Newman (Unangax̂/Deg Hit’an) and Andrea Ts’aak Ka Juu Cook (Haida) moved the event along.

the Tlingit Language

in a Pandemic

culture and Lingít Yoo X̲ʼatángi —the Tlingit language

ince the COVID-19 pandemic began, you’ve probably used video conferencing programs a lot more than normal. Perhaps you’ve held a meet-up with friends and relatives, tuned into a community meeting, or jumped around in an exercise class. But have you helped revitalize an Indigenous language?

This summer, 681 people enrolled in a Tlingit language massive open online course (MOOC) conducted via Zoom, a video conferencing platform. MOOCs are common worldwide, offering learners from disparate regions an opportunity to learn together online. The 38-hour, five-week course was offered by Outer Coast College in Sitka, in partnership with Sealaska Heritage Institute. It met online Monday-Friday evenings, offering beginner, intermediate, and advanced conversation and language instruction.

HIRLEY ESMAILKA-SAM remembers sitting outside the Koyukuk Tribal office building to access the internet for her distance education classes.

“Sometimes it would be raining, sometimes it would be cold, sometimes it would be hot,” said Shirley (Koyukon Athabascan), who is now completing her master’s degree in rural development at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. “I would have to sit outside the Tribal office building or in the washeteria so I could log into my online classes.”

Shirley’s story isn’t unique. Sluggish bandwidth speeds in rural Alaska make it necessary for some students to sit outside the entryway of their schools and Tribal offices at night to get Wi-Fi reception on their laptops to complete their homework and access their courses. Many of them work until their hands become numb from the cold making it almost impossible to type or log into online classes.

he famous Chinese proverb by Lao Tzu says, “The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step.” Those words ring true to my story. My journey from Teller to Nome began long before it started.

On a fateful night in September of 1999, I found myself on an ambulance stretcher almost lifeless. All of the screams and the scenes of people trying to save my life faded away into absolute nothingness. I couldn’t hear and I couldn’t see. It was in this dark moment that I begged earnestly, with a simple yet powerful thought, “Dear God, save me.” I was sixteen years old, depressed and intoxicated. A hunting rifle blew off point blank in my face in an attempt to end my own life. But in the midst of the unknown I wanted to live. Miraculously, I survived. Alive, but legally blind and unable to speak.

As I was struggling to breathe in the intensive care unit I fell into a vision. A thick fog rolled into the room as an old village appeared. It felt so peaceful and there was no pain. My late great-grandfathers were sitting on the ground in their bird-feather parkas beckoning for me. As their eyes beamed with pride they greeted me silently. In our Native language they explained that it wasn’t my time yet and that I needed to go back because I was going to do great things. They gave me a blessing and I returned with a new sense of purpose. I knew everything would be okay, despite the pain of surviving with severe facial wounds.

he famous Chinese proverb by Lao Tzu says, “The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step.” Those words ring true to my story. My journey from Teller to Nome began long before it started.

On a fateful night in September of 1999, I found myself on an ambulance stretcher almost lifeless. All of the screams and the scenes of people trying to save my life faded away into absolute nothingness. I couldn’t hear and I couldn’t see. It was in this dark moment that I begged earnestly, with a simple yet powerful thought, “Dear God, save me.” I was sixteen years old, depressed and intoxicated. A hunting rifle blew off point blank in my face in an attempt to end my own life. But in the midst of the unknown I wanted to live. Miraculously, I survived. Alive, but legally blind and unable to speak.

As I was struggling to breathe in the intensive care unit I fell into a vision. A thick fog rolled into the room as an old village appeared. It felt so peaceful and there was no pain. My late great-grandfathers were sitting on the ground in their bird-feather parkas beckoning for me. As their eyes beamed with pride they greeted me silently. In our Native language they explained that it wasn’t my time yet and that I needed to go back because I was going to do great things. They gave me a blessing and I returned with a new sense of purpose. I knew everything would be okay, despite the pain of surviving with severe facial wounds.

or many Alaskans, our feelings for what our state means to us are as vast as the 375 million acres of land of which it is comprised. How do we begin to describe what is wordlessly amazing about the land and waterways we travel and people we experience? What is that feeling when we step into clear view and see a vista so beautiful, it seems unreal and out of this world? The thing is, it can’t be quantified into a single feeling. The feeling is the abundance of feelings. To what extent would we go to make sure this abundance of feelings is preserved and shared with as many humans as possible for the betterment of life on earth?

This is the question posed to us in Mark Titus’s film The Wild when he asks, “How do you save what you love?”

In this case, he is referring to roughly 27.5 million acres of feelings that make up the Bristol Bay region in Alaska. More specifically, the 12.5 million acres of feelings set aside for development by the Bureau of Land Management, known as the Bristol Bay Area Management Plan. Even more specifically, it’s the 98,000 acres of feelings that have been proposed for development of the largest open-pit gold and copper mine in the entire world—known globally as Pebble Mine.

hen the 300-year-old red cedar log T.J. Young was recently carving was a seedling, a group of Haida people were making their first journey to Prince of Wales Island. The land around where Hydaburg now sits featured scattered villages behind sloping beaches, with wood smoke rising from large communal longhouses. Totem poles towered over dugout canoes parked above the tide.

Much has changed in the three centuries of that tree’s life. However — thanks to the careful stewardship and initiative of many passionate people — the bountiful natural resources of the area, and the proud arts and culture of the Haida, remain.

Over a period of four months, T.J. and three other artists have spent nearly 10 hours a day transforming that 27-foot, 30-inch-diameter log into a traditional dugout canoe.

hen the 300-year-old red cedar log T.J. Young was recently carving was a seedling, a group of Haida people were making their first journey to Prince of Wales Island. The land around where Hydaburg now sits featured scattered villages behind sloping beaches, with wood smoke rising from large communal longhouses. Totem poles towered over dugout canoes parked above the tide.

Much has changed in the three centuries of that tree’s life. However — thanks to the careful stewardship and initiative of many passionate people — the bountiful natural resources of the area, and the proud arts and culture of the Haida, remain.

Over a period of four months, T.J. and three other artists have spent nearly 10 hours a day transforming that 27-foot, 30-inch-diameter log into a traditional dugout canoe.

xidingiłq’oyh | catalyze

Flu Vaccines:

More Important Than Ever

Receiving a flu vaccine this winter may be more important than ever. The vaccine not only reduces your risk of getting the flu, but protects children, Elders, and those who are most vulnerable. The flu vaccine may also help prevent being infected with both COVID-19 and influenza at the same time, which may cause severe illness or death for those who are at a higher risk. Getting vaccinated also helps to preserve health care resources.

The CDC recommended that people get a flu vaccine by the end of October. Getting vaccinated too early (for example, in July or August) is likely to be associated with reduced protection against flu infection later in the flu season, particularly among older adults.

“Flu vaccines are safe and are the best protection to prevent getting sick from the flu, and to help protect others. Now is the best time to get a flu vaccination,” said SCF Senior Medical Director of Quality Assurance Dr. Donna Galbreath.

(Yup’ik), St. Marys, Alaska

(Yup’ik), Bethel, Alaska; may she rest in peace

3 eggs

½ C. Milk

2 T. Flour

2 C. Bread crumbs

1 T. Salt

1 tsp. Garlic salt

1 tsp. Dill

Oil for frying

Heat oil to medium-high in a large pan. Whisk eggs, milk, and flour together in a shallow bowl or pie plate. Stir bread crumbs, salt, garlic salt and dill in another shallow bowl or pie plate. Dip the halibut into the egg mix, coating all sides, and then place in the dry mix, coating all sides. Cook halibut in the oil until golden brown, about five minutes.

1 T. Dill relish

1 T. Sweet relish

1 tsp. Lemon juice

1 tsp. Dried dill

1 tsp. Worcestershire sauce

Mix all ingredients well and serve with fish.

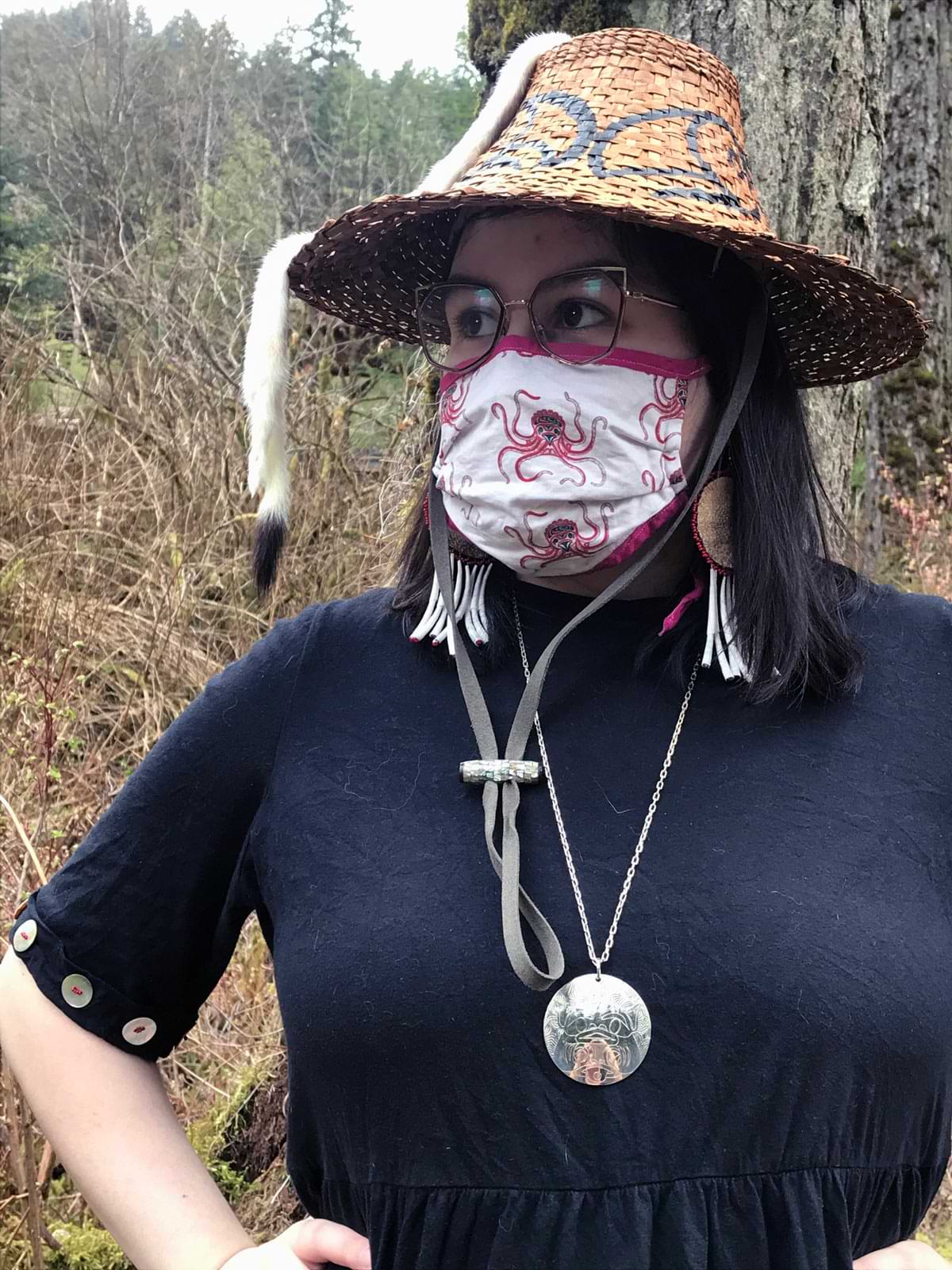

TRHT, which stands for Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation, provides for critical space for our untold truths to be shared in Indigenous-led spaces that center healing, and locally-driven transformation for a better Alaska. The time has come to grow Alaskans’ understanding of our true history, right the past wrongs that inhibit our true potential as a state, and advance an equitable future for all Alaskans. At this years Smokehouse Gala, the Trustees and Staff of First Alaskans are honored to create a new tribute for global media makers and influencers who are drawing critical light to our Native peoples here at home in Alaska and across the world.

Our peoples have always stood up for racial and social justice and our inherent right to live our ways of life, action that has taken many forms over the last century and even earlier. This special tribute to the following groups uplifts their active work to change the narrative around racial equity, uplift the brilliance of Indigenous peoples across the world, and catalyze a new understanding of the Indigenous lands upon which this country is built. These influencers use their tremendous global platforms to lift up Alaska Natives and other Indigenous peoples in solidarity, every single day; fight for racial equity; and uplift a loving and true image of our peoples and our ways of life. We honor their efforts, are grateful for their work and those that lift them up and created them. We are proud to call them our relatives.