Section and department titles are in Haida. Each issue of First Alaskans features a different Native language in this role. Thanks to The Dictionary of Alaskan Haida, by Jordan Lachler.

Patch

Work

s an act, it occurs one at a time. Picking berries reminds us to slow down, or things get missed. Berries hidden below the leaves. As my bucket slowly fills one handful at a time I wonder, what does it mean to preserve? Is it to persevere; to continue on; or overcome? Or maybe it is to outlast. Maybe in the act of preserving we hold onto something. Something is saved. An act, a value, culture, memories.

kínggwdang  STORIES FROM AROUND

STORIES FROM AROUND

Three youth in Elim save fourth boy’s life

Eklutna Tribe loses court decision for casino

KTOO reported Judge Friedrich’s judgement that the eight acres were not considered “Indian land,” and therefore Indian gaming rules don’t apply.

The federal court decision can be read here.

Tanning Fish Skin

he sacredness of salmon was not lost on me as a child; having respect for the life that sustains us was instilled into my worldview at a very young age when I first attended fish camp. However, the divinity of dry fish did not bless me until I returned to my father’s village of Akiak in the year 2006. As I sat chewing and pulling off a chunk of dark amber arid flesh with my canines, the abundance of flavors that stewed from our generational, cultural traditions was more than enough to make a foodie fall in love. The more you eat it, the more the savory mystery unfolds. When I was immersed in unlocking its hidden treasures, the faint bitterness of burnt wood stung the tip of my tongue as I attempted to consume all the oil off the skin. The cells in my body awakened, fingers anointed with lavish grease and the aroma of smoked fish.

An Act of Descent

ike many original-enrollee descendants of Alaska Native corporations, Hallie Bissett (Dena’ina) grew up around her family’s regional corporation, CIRI. But it wasn’t always clear to her what the corporation meant to her, even as a young adult.

“I was 15 years old, and as part of an internship, I worked as a grounds keeper with CIRI,” said Hallie. “I didn’t think much about CIRI or being a descendant until I worked there… [But] it wasn’t until I wanted to go to Fort Lewis College that being a shareholder became relevant.”

At Fort Lewis College Native students may attend for free. But despite Hallie being Dena’ina, a problem quickly arose regarding her identity.

Our Ways of Life

on hunting and fishing management

n September, First Alaskans Institute hosted an online event, Protecting Our Ways of Life Virtual Tribunal: Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation. The event was designed to allow Alaska Native people to speak about their experiences concerning State and Federal hunting and fishing management systems that have negatively impacted them and their communities.

The testimonials stemmed from a need to recognize and address ongoing challenges to the social, economic, and political marginalization of Alaska Native people and communities. During the event, participants emphasized specific and tangible examples of many issues that have negatively impacted them and their communities.

Homeland

f you have driven past the Anchorage Museum, you may have seen the front of the building with the enormous words, “This is Dena’ina Ełnena.” This is from the Dena’ina language, meaning, “This is Dena’ina homeland.” Years of effort went into bringing this land acknowledgment to the Alaska community.

Before statehood in 1959 and the “purchase” of Alaska in 1867, what is known as the Anchorage area already had a long and rich history. Between the Chugach and Talkeetna mountains, is home to the K’enaht’ana Indigenous people of Nuti (Knik Arm). They are members of the Eklutna (Eydlughet) and Knik (K’enakatnu) Tribes. They have been in the area for at thousands of years.

f you have driven past the Anchorage Museum, you may have seen the front of the building with the enormous words, “This is Dena’ina Ełnena.” This is from the Dena’ina language, meaning, “This is Dena’ina homeland.” Years of effort went into bringing this land acknowledgment to the Alaska community.

Before statehood in 1959 and the “purchase” of Alaska in 1867, what is known as the Anchorage area already had a long and rich history. Between the Chugach and Talkeetna mountains, is home to the K’enaht’ana Indigenous people of Nuti (Knik Arm). They are members of the Eklutna (Eydlughet) and Knik (K’enakatnu) Tribes. They have been in the area for at thousands of years.

While Anchorage and the Southcentral region are the homelands of the Dena’ina people, as recent as 2005, the city didn’t reflect its Native history. In 2006, Cook Inlet Tribal Council (CITC) opened the Nat’uh Service Center. Nat’uh is a Dena’ina Athabascan word meaning “our special place.” It was the first building in Anchorage to have a Dena’ina name.

Issue of Blood Quantum

laska Natives have been using marine mammals for food, clothing, shelter, and other necessary uses since time immemorial. Today, the use of marine mammals by Alaska Native people is becoming an act of civil disobedience due to the verbiage used in the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) enacted in 1972. The MMPA prohibits Alaska Natives under one-quarter-blood quantum from partaking in this longtime cultural tradition. Federal laws that were enacted in the 1970s purposefully do not recognize individuals under the quarter blood quantum as Indigenous. Currently, over 60% of Alaska Native people around the Gulf of Alaska are under a quarter blood quantum. With each successive generation, Alaska Natives’ blood quantum continues to decline.

The use of blood quantum to determine a persons’ degree of Native ancestry is a construct of colonization that has been long used by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The use of blood quantum came into existence in the late 1800s when federal laws were enacted to compile lists of Indigenous people. It was a way for the government to “authenticate” how Indigenous an individual was during the allotment period between 1887 and 1934. Blood quantum was used and integrated into dividing land for individual allotments. Due to the quarter blood quantum rule many were ineligible, thereby reducing the amount of land that was given to the Indigenous people at that time. Blood quantum has always been a tool used against Native people to eventually be defined out of existence. It is the path that leads to the extinction of our people, our culture, and our traditions.

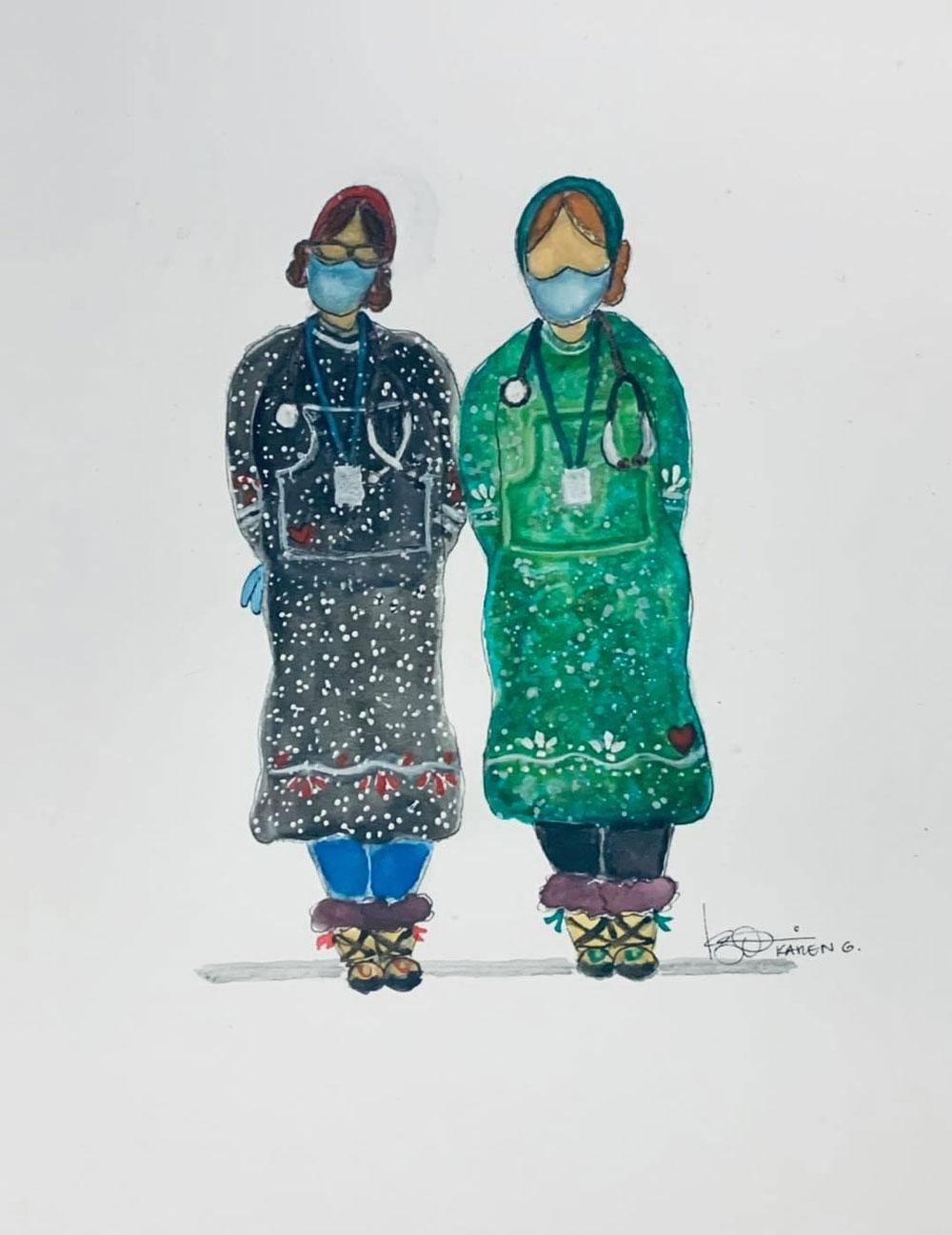

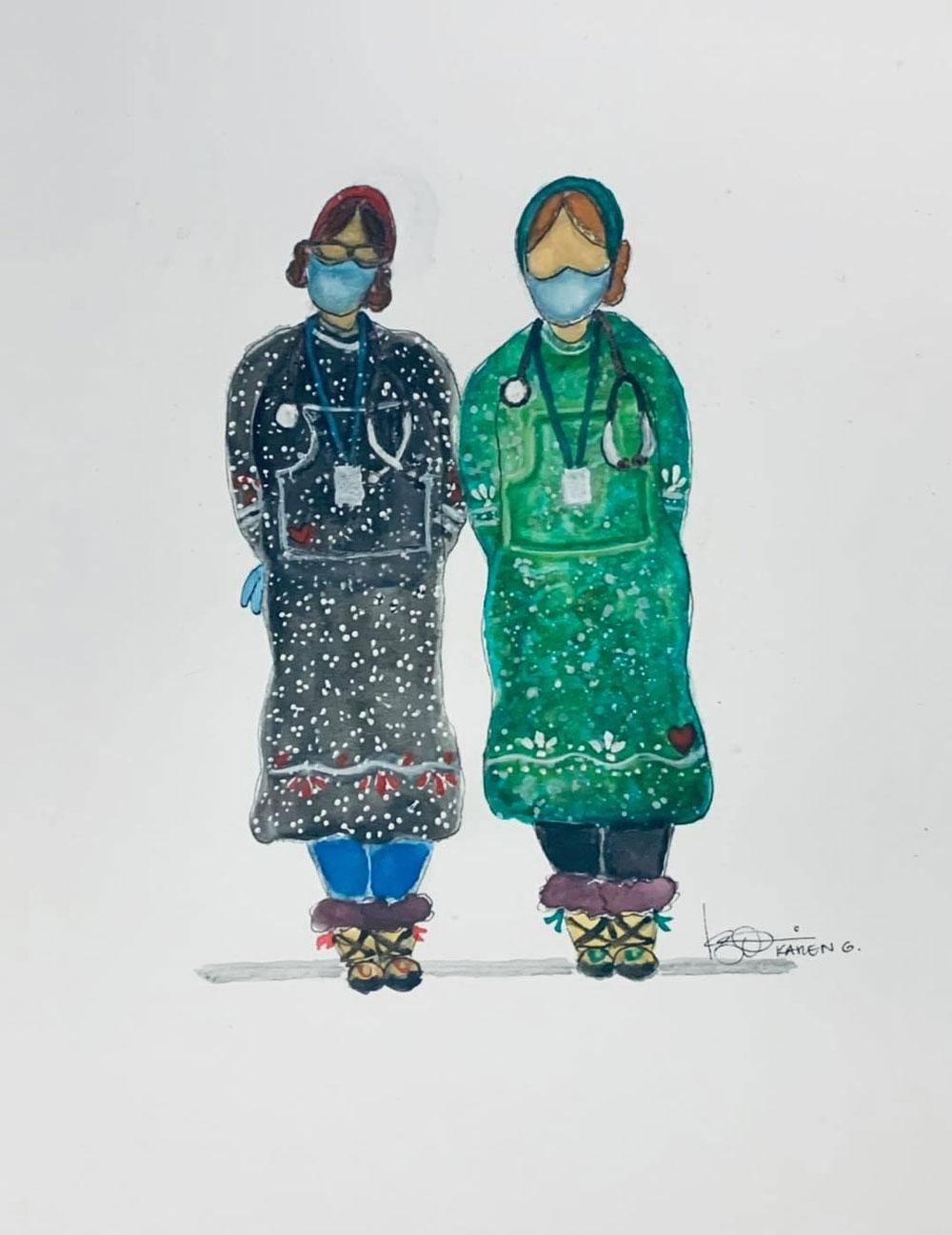

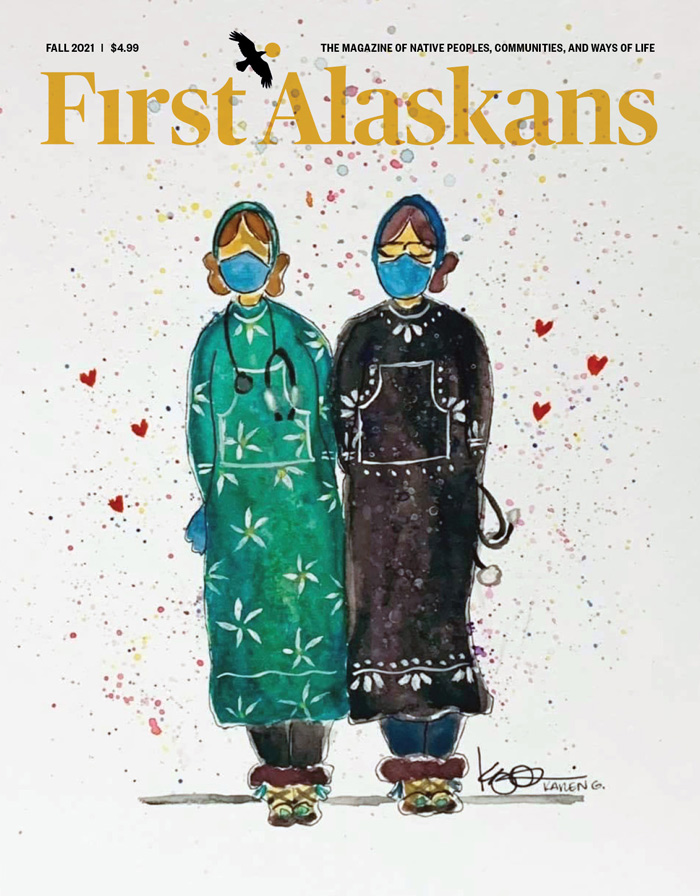

Honoring

Healthcare Workers

Honoring Healthcare Workers

To the Native health system employees who are working night and day specifically with COVID to test and vaccinate both Native and non-Native community members in entirely new systems, locations, and guidances that didn’t even exist yet a year ago — chin’an.

You are saving our lives.

To all the Native health system medical staff who have been working long shifts to keep our population healthy in a ever-changing, stressful conditions — gunalchéesh.

Your work deserves every praise and all the support we can muster.

To the Native health system non-medical staff who have been working equally long shifts to reach as many members of the community as possible, Native and non-Native, and to make sure our health system is working as efficiently possible during a worldwide pandemic — qaĝaasakung.

A Fine Balance

he strong, measured, and contemplative voice in Open the Dark, a debut collection of forty-two lyric poems, belongs to poet Marie Tozier (Inupiaq/Puerto Rican.) The book’s release in August 2020, at the height of the coronavirus pandemic, prevented Tozier from giving any public readings. The work drew attention, however, and last winter the Poetry Foundation chose her poem “Little Brother” as a Poem of the Day and included two more on its site, and Poetry Daily featured “Aakuaksrak” as a Poem of the Day.” Marie wrote the poems for her Master of Fine Arts (MFA) from the University of Alaska Anchorage, which she received in 2016.

Originally from Nome, Marie celebrates a life that harmonizes with seasonal rhythms and the land’s varied offerings throughout the year. Most of her short lyric poems focus on family, the northwest landscape, nature, seasons, gathering food, fishing and hunting. Other poems, however, highlight the challenges and problems that beset Native people. The writing, subtle and restrained, explores joyful moments, personal traumas, memory and loss. The language is accessible and clear but with layers of complexities and meanings.

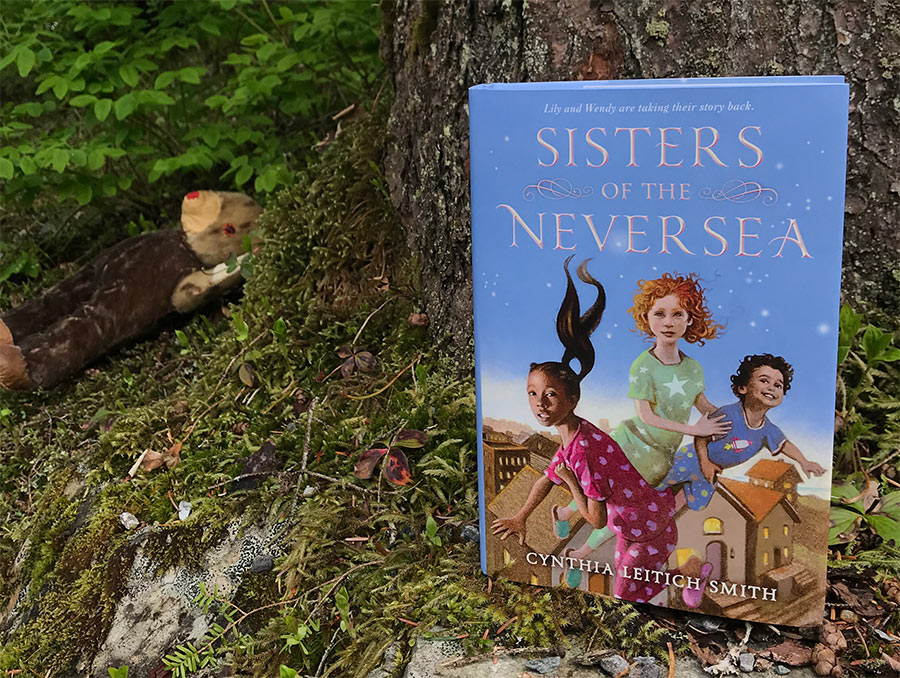

Reads and Reviews

By Cynthia Leitich Smith

(Muscogee Creek Nation)

What Cynthia Leitich Smith (Muscogee Creek Nation) has created is much more than a retelling, however. She’s written a new story that stands on its own. Of course the answer was to have an Indigenous person re-write the story and reclaim the narrative. I loved the two sisters who are grappling with a shift in their family structure and trying to figure out how it will change their relationship. There was a great representation in all of the Neverland characters from the Lost Boys, the Native kids, and pirates. I appreciated the characterization of Peter Pan as the source of everyone’s problems, which is a shift I’ve seen in a couple other retellings… and honestly the only way it makes sense to me now. In terms of the writing style, I really enjoyed the use of third person narration for the book. It felt very much like we were being told a story, and the storytellers were the stars.

The Future Looks Bright (And Pretty Cute!)

below: Rylan Campbell from Gambell (St. Lawrence Island Yupik) takes a little taste of some good Native food. Photo courtesy of his mom, Apaay Campbell, and grandma, Sharon Aningayou.

bottom: Bryanna, Davena and Avery are three Inuvialuit girls from Tuktoyaktuk, in Canada, who have some great gear to fight mosquitos while they pick berries. Photo courtesy of their grandma, Marilyn Cockney.

The Future Looks Bright (And Pretty Cute!)

ñánga | Imagine

Chairman

Sam Kito, Jr. (Tlingit)

Vice Chairman

Valerie Davidson (Yup’ik)

Secretary/Treasurer

Sven Haakanson, Jr. (Sugpiaq)

Sylvia Lange (Aleut/Tlingit)

Oliver Leavitt (Iñupiaq)

Georgianna Lincoln (Athabascan)

Morris Thompson (Athabascan)

In memory of Byron Mallot (Tlingit) and Albert Kookesh (Tlingit)

(Haida/Tlingit/Ahtna)

Alaska Native Policy Center Director

Karla Gatgyedm Hana’ax Booth (Ts’msyen)

Indigenous Leadership Continuum Director

Amanda Khaa Saayi Tlaa Bremner (Tlingit)

Indigenous Advancement Director

Meritha Misrak Capelle (Inupiaq)

Gyedm si ndzox

Eliabeth Uyuruciaq David (Yup’ik)

Financial Director

Hannah Egaghaghmii (Siberian Yupik)

Ikayuq

Angela Łot’oydaatlno Gonzalez (Koyukon Athabascan)

Indigenous Communications Manager

Indigenous Knowledge Advocate

Oliver Henaayee Irwin (Koyukon Athabascan/Inupiaq)

Indigenous Knowledge Advocate

Shawaan Ch’aak’tí Jackson-Gamble (Tlingit/Haida)

Indigenous Stewardship Fellows

Anthony Khaakhootee Lindoff (Tlingit/Haida)

Indigenous Stewardship Fellows

Melissa Silugngataanit’sqaq Marton (Sugpiaq)

Indigenous Operations & Innovations Director

Elizabeth La quen naáy / Kat Saas Medicine Crow (Tlingit/Haida)

President/CEO

Ayyu Qassataq (Iñupiaq)

Vice- President

See page 24.

Anchorage, AK 99501

advertising@firstalaskans.org

First Alaskans Magazine is published by

First Alaskans Institute. © 2021.

(Tlingit/Dena’ina Athabascan)

Karen Garcia (Eben)

Raven Madison (Eyak)

Richard Perry (Yup’ik/Athabascan)

Peter Williams (Yup’ik)

Silas Tikaan Galbreath (Ahtna)